Hidden in Plain Sight

by Alan Hess

The names of countless modern architects have faded into the mists of time. Once in a while, however, one of these forgotten architects will reemerge, becoming part of a larger conversation, especially if one of his or her buildings is fortunate enough to have survived and has captured our attention with its remarkable character.

Webster and Wilson are among such architects; and the Wade House, a 1939 residence, is one of those buildings that have claimed a long-overdue spotlight. Erle Webster (1898-1971) and Adrian Wilson (1898-1988) are not as famous as other modernists—Richard Neutra, Rudolph Schindler and Craig Ellwood come to mind. Yet, Angelenos know their work without knowing their names: How many have enjoyed the restaurants, galleries, and neon-trimmed pagodas of New Chinatown on Broadway? How many have sat on juries at the Stanley Mosk Courthouse on Bunker Hill? How many have attended Comic-Con at Anaheim Convention Center? Webster and Wilson were responsible for these edifices, as well as many others.

They were architects with a wide range of abilities, designing handsome residences whose photographs were published in major magazines, handsome commercial buildings, progressive public-housing projects, and major civic landmarks. They practiced a moderate modernism that is not often celebrated today, but which remains an important part of Southern California modern design.

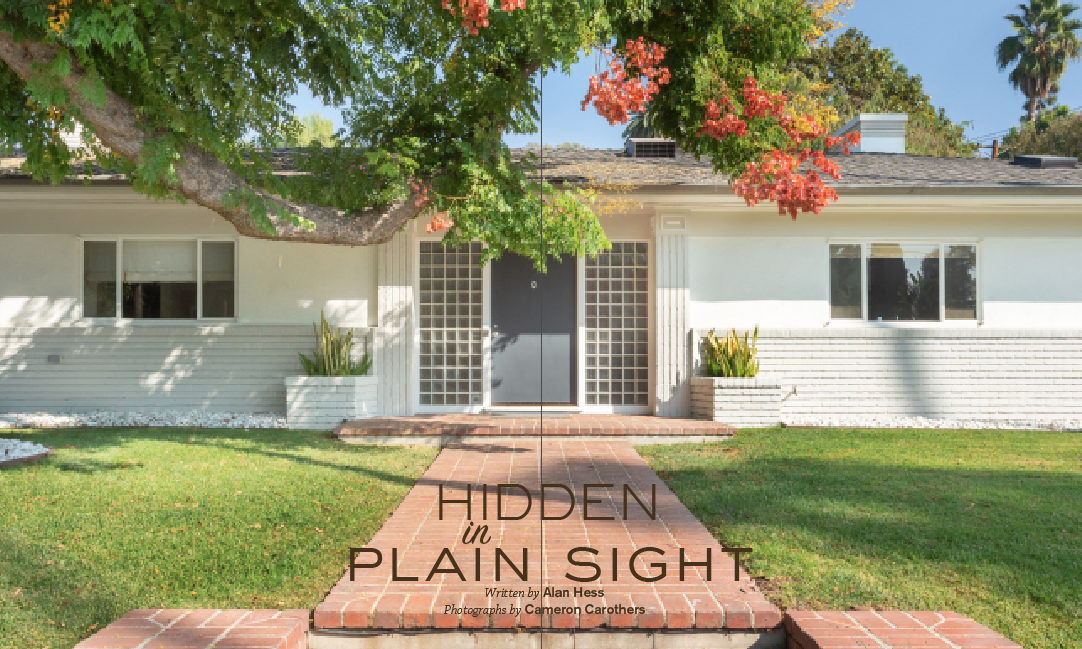

For this reason, it is worth taking a closer look at Webster and Wilson’s Wade House, which sits in a ravine north of Franklin Avenue, and beneath the famous Hollywood sign.

At first glance, the house is unassuming: A one-story ranch-style home with a long pitched roof, a low brick foundation wall, and a wide front door flanked by glass block, a hint of its 1930s construction. In fact, it might be easy to drive past until one takes a closer look. It is not Spanish, nor a cozy Tudor cottage, like others in the neighborhood. The long horizontal lines and wide eaves reflect the influence of Frank Lloyd Wright. The house is modern in character, though not stridently so.

Its modernity is even more evident inside. The plan is open. Living room and dining room flow together and out to the backyard through a wall that is mostly glass. Wide French doors unite the house with the garden, its loquat, kumquat, and orange trees promising a moment with nature. Built-in furniture promotes efficiency and simplicity. Natural sunlight, modulated by the wide eaves, fills the space. Webster often collaborated with his wife, interior designer Honor Easton, to coordinate the furnishings and colors of their house designs. Textured natural materials such as brick, grasscloth, bronze, and unpainted rotary-cut plywood show off the house’s inherent beauty.

The hearths and bookshelves in both living room and study proclaim Webster and Wilson’s modern aesthetic. Without a hint of the formality we would find in a Colonial hearth, these are sophisticated asymmetrical compositions of horizontal lines, projecting planes and receding voids, abstract arrangements of brick, plaster, and richly grained plywood. They are cubistic and untraditional, echoing contemporary designs by Schindler and Gregory Ain.

The result is a moderate modernism shaped by the character of the region. It shares the simplicity and functional design ideals of avant-garde modernism, but with its pitched, rather than flat, roof it is a gentler version. It proved more widely popular with many modern clients.

“It looked like a house, not a machine for living in,” notes architectural historian Meredith Clausen, who lived in the Wade House with her parents. The dwelling represents a distinct chapter in the story of California Modernism. Architects such as Webster and Wilson, Sumner Spaulding, H. Roy Kelley, Kem Weber, Wallace Neff, and Paul Laszlo helped developed this style.

LIVING A MODERN LIFE IN A MODERN HOUSE

The house’s expression of modern ideals attracted the successive owners of the Wade house. Each family was progressive and artistic. Over the decades, Webster and Wilson’s architecture proved the ideal stage for each family’s idea of California’s good life.

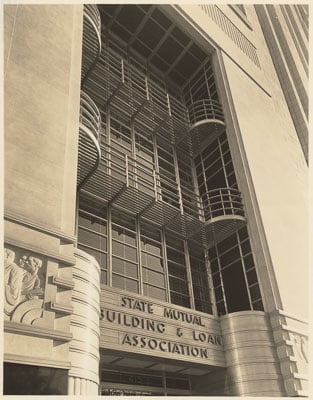

Let’s start with Webster and Wilson’s original clients, Charles and Margaret Wade. Both were solid citizens who, if they had lived back east, might well have taken up residence in a traditional Colonial house. Charles Wade was the president of the State Mutual Building and Loan Association, a partner in a general insurance agency, and a member of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. Both he and Margaret took on solid civic roles: He was director of the Hollywood Hospital and a member of the Fox Hills Country Club. Margaret was an active supporter of the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra.

But in California, a traditional, conservative home was not required for the president of a building and loan company. People moved to California to enjoy the informal lifestyle that the architects’ open plan, generous use of glass, and openness to the garden’s fresh air and plantings allowed them to do.

Charles Wade apparently first met Webster and Wilson around 1930. The architects were both working for Dodd & Richards, an architectural firm, when Wade’s State Mutual Building and Loan Association hired the company to design their headquarters. Webster and Wilson likely had a role in its plan and construction. Unlike most of Dodd & Richard’s work, the State Mutual building was a striking modern design with a prominent monumental presence on Pershing Square. Even though it was flanked by much taller buildings, it still needed attention. A four-story squared-off arch was carved out of its center to create a focal point on the entry. Although the walls around the arch were planar, a chaste cornice line of vertical lines was cast into its top floor. The designers added a subtle touch in the tubular metal balconies that crossed each of the upper floors in the squared-off arch. Inside, long streaming lines were complemented by modern chandeliers, furniture, and murals.

Wade must have liked what he saw because a few years later he hired Webster and Wilson (who formed their partnership in 1930) to design his home. The simplicity of the State Mutual building’s civic design is reflected in the residential design.

Sadly, Charles Wade died the year the house was completed, and Margaret died just two years later. The house then passed to Marguerite and Tony Staude, who lived there for twenty years. Marguerite was a local artist who crafted jewelry and sculpted busts in cast resin, many on display in the house and garden. Fully appreciating the modern character of the house, the Staudes hired Garrett Eckbo, a leading modern landscape architect, in 1948 to redesign the garden. In 1952 they added a studio.

Marguerite Staude was deeply committed to modern architecture; she saw it as a way to enrich life. Fostering the dream of building a modern chapel to inspire and uplift, she worked for almost twenty years to procure a site, funding and an architect to make that dream a reality. Today, the Chapel of the Holy Cross in Sedona, Arizona, built in 1957, stands today as one of the most recognizable modern churches in the world. This striking concrete structure with canted concrete walls rises from Sedona’s rugged red rock cliffs. Its symbolic cross, integrated into the concrete structure, grows from a cleft in the stone cliff. For the design she had chose another innovative architect, San Francisco’s Anshen and Allen, whose work spanned from this symbolic expression of spiritual ideals to the practicality of affordable, mass-produced, well-designed suburban homes for builder Joseph Eichler. In this case, good architecture—and its appreciation—begets good architecture.

In 1961, the Staudes subdivided the Wade House’s large lot to build a new house for themselves. Wanting to ensure that their future neighbors would be compatible, they sold the Wade House to their good friends Leslie and Margaret Clausen, who lived up the street. The Clausens also appreciated modernism. Leslie and Margaret Clausen had been married in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House in Los Angeles in 1938, and they were friends with Richard and Dionne Neutra. Leslie was the chair of the music department of Los Angeles City College, promoted jazz and nurtured promising students, including Herb Alpert, Jerry Goldsmith, and Jack Sheldon.

The Clausens’s social circle drew from the avant garde art world, including the Neutras, Igor Stravinsky, Arnold Schoenberg and Thomas Mann. The Clausens held regular chamber music parties for their friends, and the house’s open plan and the wide doors that allowed the living room to open to the garden were ideal for these events. Four or five quartets or trios played throughout the house and yard, with room for Leslie’s Steinway.

The Clausens’s daughter, Meredith, became a noted architectural historian and professor who wrote the definitive book on Oregon modernist Pietro Belluschi. She still speaks vividly of her family’s life in the Wade House.

WEBSTER AND WILSON’S CAREERS

Erle Farrington Webster, born in Texas, came to Los Angeles in the late 1920s. (Little else is documented about Webster’s early life.) Adrian Jennings Wilson, born in Missouri, attended St. Louis’ Washington University School of Architecture, before arriving in Los Angeles. He joined Webster at Dodd & Richards.

Although Webster and Wilson’s partnership lasted for less than a decade, they produced several notable residences and handsome commercial buildings. Their work was published regularly in Sunset magazine and Architectural Forum. Few other records exist to tell us about their work, so we are left to discover what we can from their remaining buildings and photographs. The Wade House reveals their sympathy with the currents of modern architecture that coursed through Los Angeles and the rest of the nation throughout the 1930s. Their other known houses in the area, the Ian Campbell house in Pasadena, and the Motorcourt House in the Hollywood Hills, reflected similar ideas.

Yet clearly Webster and Wilson were not rigid doctrinaire modernists. A house that showed their creative breadth was the Streamline Moderne “Ship of the Desert” house in Palm Springs, built in 1936. With a touch of poetry, the house evoked an ocean liner launched on the vast desert. Trim pipe railings on the balconies echoed the decks of the Île de France, and porthole windows added a whimsical modernism for a carefree vacation home, without tipping over into caricature. The windows of the panoramic semi-circular living room disappear entirely into the floor, leaving the main salon open to fresh air and scenery.

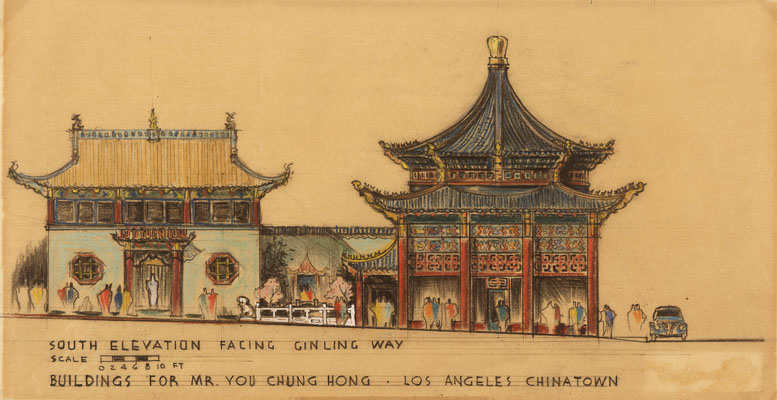

Always showing their creative flexibility, Webster and Wilson followed a different direction for the New Chinatown development in 1939. L.A.’s original Chinatown had just been bulldozed for the new Union Station. A group of Chinese-American businesspeople lead by You Chung Hong (the first accredited Chinese-American lawyer in California) bought land a few blocks away on Broadway to create a new Chinatown for their businesses and cultural activities. Just as the re-imagining of nearby Olvera Street a few years before had celebrated the Hispanic history of L.A. (mostly for the benefit of tourism), New Chinatown was a business venture for tourists and locals. With input from You Chung Hong’s wife Mabel, Webster and Wilson planned and designed modern structures that echoed the motifs of traditional Chinese architecture. These new Chinatown buildings had strong symmetries, octagonal windows and ornamental screens. But it was the neon trim that followed the upturned eaves of the classical Chinese designs that gave these silhouettes a freshness and sparkle.

The East Gate (1938) was dedicated to Lee Shee Hong, You Chung Hong’s single mother. Among several buildings Webster and Wilson designed was the Hong Gallery with wood screened windows, tan brick, and upswept roofs over windows on first floor. You Chung Hong’s law offices and the Joy Yuen Low restaurant were anchors of this complex. The well-planned urban expanse welcomed visitors to a broad plaza, while smaller courtyards and pedestrian walks, dotted with decorative pools and plantings offered quieter spaces.

For orthodox modernists, this direct appropriation of historic styles was anathema. But for Webster and Wilson—and other Los Angeles architects working in the shadow of Hollywood—this cultural layer was a valid element to inspire a design. Noted modernists such as Harwell Hamilton Harris, Cliff May, and Frank Lloyd Wright borrowed freely from Japanese, Spanish, and Mayan architectural sources. New Chinatown’s buildings, still standing today for their original purpose, have been widely popular with movie stars, artists and lay people alike.

After their work on New Chinatown, the two architects dissolved their partnership and embarked on different paths. Webster specialized in residences, and remodels, renovating a 1904 Greene and Greene house in Long Beach in 1953. In 1956, he moved to Evanston, Illinois, returning a few years later to live in Northern California. Little is known about this period of his career.

Wilson moved on to design larger public projects in L.A., eventually opening offices in several cities. He brought the simple lines and moderate modern details of his custom houses to Hacienda Village, a public housing project in south Central L.A. built for defense housing. For this early 1940s development, Wilson collaborated with Paul R. Williams and Richard Neutra.

Wilson went on to design two major Los Angeles civic landmarks on Bunker Hill, the County Courthouse (1958, now the Stanley Mosk Courthouse) and the County Hall of Administration Building, collaborating with architects Paul R. Williams, Austin, Field and Fry, and Stanton and Stockwell. These handsome Late Moderne buildings flanking Grand Park expand the moderate modernism of the Wade House to a civic scale: simple horizontal planes of terra cotta accented by bezeled window frames are contrasted with richly-colored polished granite, sculptures, modernistic loggias and entries, with terrazzo floors and stainless steel railings, balustrades, and escalators inside.

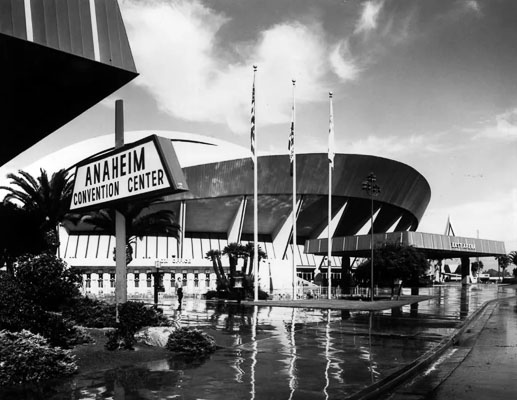

With his firm growing in size and technical proficiency, Wilson heartily embraced a bold, expressionist Modernism in two more major civic landmarks. For Las Vegas’ new Convention Center (1959) he designed an enormous saucer-shaped dome that matched the optimistic view of the future seen in Las Vegas’ hotel and casino architecture in the 1960s. He followed this with an equally bold circular convention center in Anaheim (1967) with what seemed to be flaring wings held down by a wide strap from side to side.

Although his projects grew in scale, Wilson still managed to design a residence that had an intriguing modern character. In 1954, the Western editor of Popular Mechanics magazine asked Wilson to collaborate with engineer Eugene Memmler using the latter’s modular steel frame structural system. Many architects and engineers in the postwar era believed that steel was the solution to affordable, mass-producible housing, as seen in the Case Study houses of architects Craig Ellwood and Pierre Koenig, and the Alexander Steel houses in Palm Springs by architect Donald Wexler and engineer Bernard Perlin. Like the Wade House fifteen years earlier, the back wall of the house was mostly glass, opening up the garden to daily life.

Webster and Wilson’s ultimate legacy is still unknown. Wilson’s Las Vegas Convention Center has been remodeled into an unrecognizable form. Thankfully some knowledgeable architecture patrons have acknowledged the value of their work: even after a disastrous fire struck the Ship of the Desert in 1999, owners Trina Turk, the fashion designer, and her late husband Jonathan Skow rebuilt the house with great care. The Wade House still retains much of its original appearance, and its interior remains largely the same, save for a few modifications, such as a remodeled kitchen and breakfast room. New Chinatown still stands, and has enjoyed a surprising new life thanks to an influx of artists and galleries. Our knowledge of New Chinatown is enriched by original drawings now held by The Huntington Library. Of course, there is always the possibility that unrecorded examples of Webster and Wilson’s work remain to be discovered.

The skill of these architects is evident. Webster and Wilson’s modernism deserves attention alongside the better-known modernist landmarks of Neutra, Wright, and Schindler. Although some critics might doubt their modern credentials after seeing the oriental flourishes of New Chinatown, the fact remains that a purist attitude was not required of modern architects, especially in California. Webster and Wilson prove the lasting value of this approach.

Contact us about this property:

Error: Contact form not found.