The Art of Mastering the Slope

Never one to run from a creative challenge, Rudolph Schindler proved he could conquer hillside terrain with his innovative Kallis House in suburban Los Angeles.

by Nicholas Olsberg

As our perspective on mid-20th-century Los Angeles grows with the passage of time, we are quicker to recognize that its experiments in modern living were as vast as they were varied and the work of its master builders was uncommonly distinctive. Certain fundamentals characterized the California modern house and many were adopted world-wide: the open plan; the ease of movement between inside and out; the division of the garden into zones for outdoor living; the increase of living space within a small structure by eliminating many traditional features, such as basements, hallways, and attics. But the leading figures in the first 15 years of postwar California architecture—Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, John Lautner, among others—were not only united by an adherence to this common language, but by the different and often highly original ways in which they spoke it, from the simple tongue of Raphael Soriano to the high drama of Lloyd Wright.

At the time, there were particular conditions in Southern California that encouraged this supply of seemingly inexhaustible originality and invention. As the post-war development and suburban sprawl of Los Angeles spread to steeper and more intractable sites, architects faced engineering challenges and planning opportunities for which few rules or conventions existed. Highly irregular sloping lots presented extraordinary challenges for which architects sought solutions: Maximizing vistas by inverting the usual sequence of entry, living, and sleeping spaces; reimagining house plans to suit the slope, either by condensing them in order to float the structure on a raised platform (e.g., John Lautner’s spaceship-style Chemosphere house in the Hollywood Hills) or by creating dwelling zones that follow the lay of the land—as Rudolph Schindler chose to do in 1946 with his innovative Kallis House in suburban Studio City, California.

Such invention depended as much on adventurous clients as on imaginative architects and this was another advantage of the L.A. landscape that contributed to the rethinking of spatial and visual patterns in the modern home. There were the engineers of the burgeoning aerospace industry, the designers and artists who toiled at the movie studios in what was arguably their heyday and the presence of a Bohemian sub-culture open to new and more casual ways of living. All these factors were enough to produce a small but significant pool of clients as ready to live in an experimental structure as the architect was to design one. As Lautner once noted, it was his clients’ openness to new ways of living that compelled him to stay in L.A.: He simply could not have done what he did anywhere else.

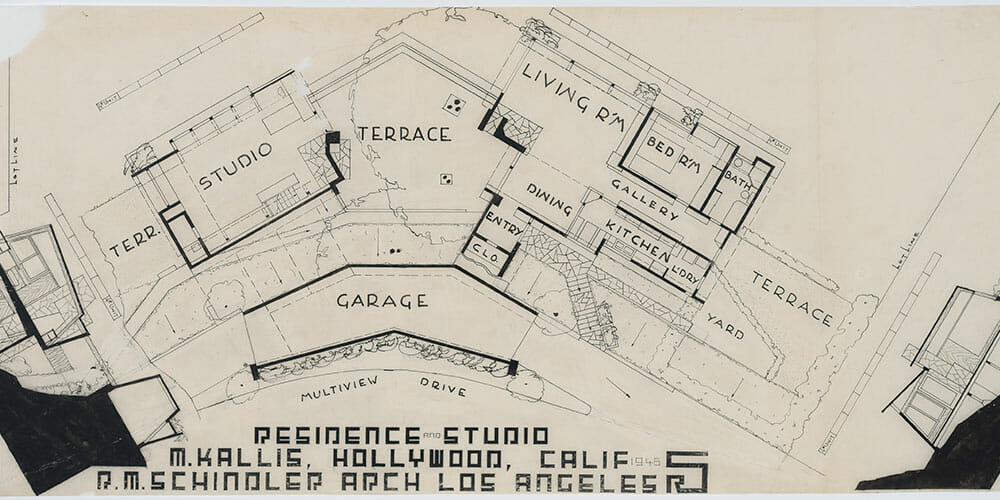

The same could be said of Rudolph Schindler and the Kallis House. In many ways, the Austrian-born architect was the most brilliant and consistently inventive of L.A.’s modern masters, not to mention he was the eldest and most practiced among them. In a famous phrase, the distinguished English architectural critic Reyner Banham described Schindler as designing houses “as if there had never been houses before.” No two were quite the same and none looked like anything anyone had seen or lived in before. Among them, the house and studio he designed for the artist and Hollywood art director Mischa Kallis, built in the first year of peacetime California, is perhaps the most strikingly original of all—it is set high on a slope, twisted and divided into segments to meet the curve of the road and the shape of the lot. It not only reinvented the relationship of indoors and out, upstairs and down, but it was constructed with incredible complexity through the simplest of building methods.

Born in 1887, Schindler had studied and apprenticed in Vienna and was profoundly affected by the emerging theories of Adolf Loos, Josef Frank, and others, who were proposing a new stripped-down simplicity to the texture and scale of the home, while advancing new ways of thinking about the house and its rooms—what Frank called a journey of constant discovery within the smallest of shapes. Schindler arrived in Chicago shortly before the outbreak of World War I and soon found himself working for Frank Lloyd Wright, eventually taking over the office during Wright’s absences. Little noted, but central to the rest of his career, was his extensive work on what remained the largest single project in all of Wright’s work—the “ready-built” American System Homes, in which dwellings of every scale and context, many of great complexity, were constructed from the same pre-cut repertory of components in a system of frames and panels. He shared with Wright, too, an almost missionary belief in architecture and especially the reform of the home as a social, moral, and cultural force rather than a mere matter of convenience and design. Wright talked of making the home “a place for the growth of the soul,” and Schindler of “the building as a frame… a cultural agent—stimulating and fulfilling the urge for growth and extension of our own selves.”

It was their mutual opinion that houses, as in the American System, must be made simply, economically and with readily available building materials and construction techniques. It is that balance between poetry and practicality, complex spatial journeys made through simple constructional means, that Schindler set out to achieve from the start of his independent career, with his own dual concrete-and-glass house at 835 North Kings Road in West Hollywood—now an L.A. landmark. Through the 1930s, he continued to explore this in many small-house experiments with panel systems, culminating in two series of “Schindler Shelters,” designed for prefabrication in different materials and at different scales.

By 1946, Schindler had moved firmly in another direction in which the house is not delivered as a kit, or designed from standard pre-cut panels, but developed on and for its site. Rather than a system or a single mathematical module, he produced unique solutions, using standard board dimensions and familiar joinery techniques to ensure their rapid and efficient construction. Furthermore, he used plain boards to avoid the cost of plaster and often created cladding—as he did with the Kallis House—using rough-and-ready materials from builders’ yards, sourcing commonplace materials at garden and hardware stores and adjusting the design as the framework, space and light unfolded before him. Noted architectural historian Esther McCoy, who worked with Schindler at the time, recalled that this mode of working was a source of endless delight for him as he sketched a plan that had never been seen before on to a site map, or laid a board at an immeasurable angle to form a wall.

To explain the thinking behind such works as the Kallis house, Schindler defined a number of general principles. Houses must avoid any “stereotyped vocabulary of steel columns, horizontal parapets, and corner windows.” Those produced something “essentially one-dimensional, whereas the house as an organism in direct relation with our lives must be of four dimensions” in which “every detail, including the furniture, is related to the whole and to the idea which is its source.”

He went on to say how each element should be treated. The floor “is understood to be part and continuation of the ground outside” and should be carried through in hard finishes to achieve that. Furnishings must “merge…with the house, leaving the room free to express its form.” Doors are there “to walk through rather than to form an impressive frame for one who carefully pauses on the threshold.” Roofs, increasingly important to Schindler, are to “shelter us instead of crowning our position,” and the meeting of wall and ceiling should create the essential flow of light between spaces, drawing the eye to the roof above and producing “a natural interlacing of the areas of communication” that are sheltered under it. Windows “must minimize window-heads to maximize continuity.” Light should “permeate space, give it body, and make it as palpably plastic as is the clay of a sculptor.” Structure must be made plain, no beams hidden, and the logic of the construction evident. In this way, the whole will have a rhythm that is not artificially set up by the repetition of a fixed unit of measure, “which creates texture rather than rhythm” but by “related spacings,” so that the house will become like a piece of music, its tempo and phrases interlocking into a single coherent “space-frame” with a logic that is unique to it.

These are complicated notions and they may produce work with extraordinary underlying complexity. They are dependent, as he said, not on models or perspective drawings, which he rarely produced, but on what was “visualized and created in his mind.” For the Kallis House, Schindler drew 17 different sections on one sheet just to begin to express the shapes of the spaces and to demonstrate what united them—in this case a series of two-foot intervals, like the staves of a musical score, which he drew beneath each section and which is reflected in all dimensions as he averaged his ceiling heights to eight feet and varied each component on the same division of 12. The framing and supporting system (which can be seen in the marvelous model of the Kallis House built by students at Cal Poly Pomona for the Pacific Standard Time art exhibition held in 2011) is even more complex. Yet the result—with its sloping walls, changing heights, mingling of rough to smooth, interlocking space, and interlacing light—has a sense of improvisation and feels extraordinarily simple, light, and alive, like a sculpture made of empty space.

“He designs and builds in space forms rather than mass forms,” McCoy wrote in 1945 as Schindler produced sketches of the Kallis house, according to Susan Morgan’s book, Piecing Together Los Angeles: An Esther McCoy Reader. “His houses are wrapped around space. A Schindler house is in movement; it is becoming. Form emerges from form. It is like a bird that has just touched earth, its wings still spread.”

The Kallis House, perhaps more than any other of his masterworks, carries that joyous sense of becoming. To use the kind of musical analogy he favored, it seemed to welcome that first year of world peace and to celebrate the life of the family who would reside in it as a kind of scherzo—a fast-moving composition performed in a playful manner. It is an increasingly famous work that students of architecture throughout the world study and learn from and has been referred to as “an exploded box with slanted walls and angled roofs and trapezoidal windows.” With its raw, unfinished quality, it was an enormous influence on Frank Gehry, who studied it at USC in the 1950s.

Over time, the home has stayed essentially within two branches of the same family—the Kallises, who were devoted to visual arts and the Sharlins, who were dedicated to music. Clearly, it has been much respected and loved. For many years, it survived unchanged. Even with the eventual enclosing of the patio by the talented modernist Josef van der Kar and the quiet conversion of the studio to the master bedroom by Leroy Miller, Schindler’s original concept has remained firmly in place. Most of his cabinetry is still there and the furnishings reflect his preference for muted colors and are carefully positioned to harmonize with the architecture. As a result, if there were ever one house that best expressed Schindler’s optimistic vision of an architecture that was the agent of a free and creative life and a demonstration that such a thing could indeed exist, this casual, playful and wonderfully livable masterpiece just might be it.