Laboratories for Living

by Nicholas Olsberg

Nothing seems to get the juices of architects flowing more freely, nor tempt them to break as many rules, as the idea of the house. For more than a hundred years, from the first experiments in open plan living to the latest adventures in lightweight dwellings and tiny houses, the modern home has been the testing ground for new ideas in architecture.

For some designers, that has been a matter of trying out ways to match the shape of buildings to new patterns of life. For others, houses have allowed them to test new structures, materials and systems with a freedom that is unimaginable in a public or commercial building, where design must meet the demands of a fixed program, the economics of tenancy, and a legion of clients, approvals and regulatory restrictions. Still others have found in the forgiving scale of the house and its inevitable relation to the land- scape an opportunity for flights of fancy – to play with a formal notion or an improvisation, as Mozart would write a fantasy or Schubert an impromptu. But for all, the house has been an endless challenge to innovation and inspiration.

Like the chair, at which almost all great modern architects have tried their hand – thinking of new shapes to embrace the body as life and relaxed manners began to value comfort, and of new materials to mold those shapes with – the home has been constantly reconfigured to meet the changing habits of a household, and the patterns of leisure, work, and movement that it follows.

THE MANY WAYS TO BE MODERN

This issue of architectureforsale quarterly looks at four masterly but very different examples of these experiments in modern living. The earliest is a Greene & Greene house that catered to the growing informality of life in California at the dawn of the modern era, as the age of grand entry halls, nurseries, ballrooms and parlors gave way to an era in which well-to-do families lived with fewer servants, shared their living space with children, welcomed visitors to their everyday quarters, took their ease in company (rather than sitting on stiff backed chairs), and wandered through house and grounds, indoors and out, in the same clothes.

One was built as the Baby Boom ended among a cluster of middle class homes by Richard Neutra that – in the age of La Dolce Vita, Playboy, and Ocean’s Eleven – began to weave into the studied compression and simplicity of the Modern house a new taste for what was then called ‘sophistication,’ a sense of refinement, permanence and modest luxury, in which the plan of the home began to spread more generously and to gently separate grown-up activities from family mayhem. Another, John Lautner’s astonishing space-age Silvertop, sought an altogether new kind of serenity and grandeur, in which the house was shaped as a sort of observatory – a fantasia in which the house became a transcendent space for the enjoyment of changing light, distance, and vista, and the unchanging geometry of the universe. All were laboratories in the imagination of an ideal living space. All grow from the fertile social landscape of southern California.Yet none are remotely alike.

As time passes we begin to sort our built history into categories – like the ‘Craftsman Bungalow’ or the ‘Mid-Century Modern House’ – and I am sure we will soon be finding an equally useful term to embrace the ruggedly inventive live-work spaces of the ‘80s and ‘90s. But in classifying things that way, we are in danger of thinking about them as if they were cookies pressed through the same cutter and are then tempted to re-do and furnish them in some generic fashion that seems true to our ideas of what characterizes a style. What can get lost in that process is the distinctiveness, the idiosyncracies behind the work of great designers, and the very specific solutions they found for each client, moment and situation.This is not a matter of a signature feature – like a Wallace Neff arched window or a touch of Frank Gehry mesh – but their voices, their separate and even disparate ways of working, even with the same materials, in the same broad terms, and toward the same purpose.

There is as much variety in modern architecture, especially in its reinvention of the home, as in modern painting or modern music. Charles Greene is no closer to Irving Gill or Frank Lloyd Wright than Stravinsky is to Béla Bartók or Schoenberg. Lautner is no nearer Neutra than Rothko is to Pollock. We run the risk of neutralizing their works the moment we start to recast them from a common mold and then are caught short by the originality of the real thing, especially in those rare cases where every detail of the original design remains intact. As Barbara Lamprecht makes clear, this is not just a matter of differences between designers, but of decisive differences between their works, even when – as at Neutra’s Kambara house – the building in question is both part of a unified group and the product of a standard system or ‘kit of parts’. To stretch the musical analogy further, a masterly technique will ring endless variations even on a single theme.

THE EXPERIMENTAL HOUSE

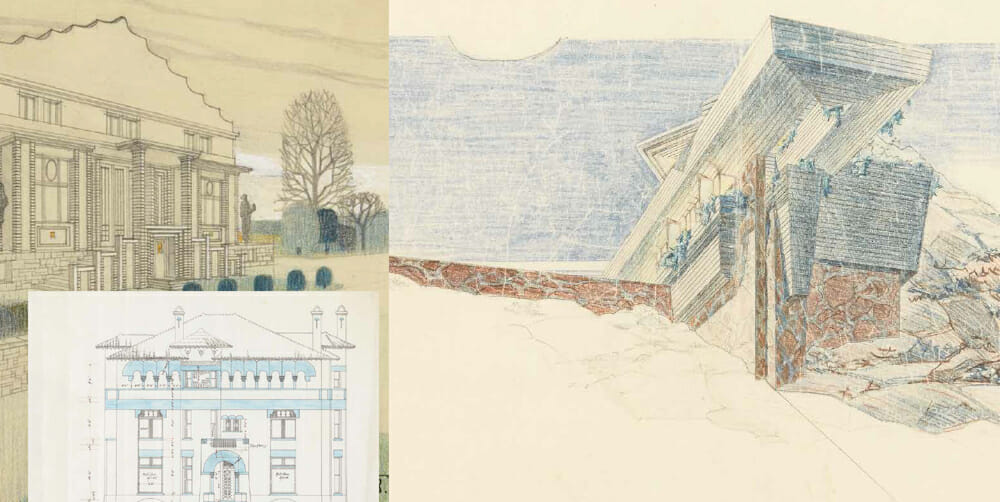

Here, taken almost entirely from a private collection in London, we trace through drawings and models – the mind’s eye of the architect – at four key points in time along this immensely varied experimental line. Some are solitary ventures into the realm of invention in which the design is governed by the specifics of a site and client, some are conceived as prototypes for a new house type, and yet others use the house to express an idea or explore a line of inquiry about the very shape and nature of architecture and its place in the landscape and culture.

The first comes at the dawn of theTwentieth Century as students in the Vienna school of Otto Wagner – establishing a modern tradition from which L.A.’s Rudolf Schindler and Richard Neutra derive – began to look at ways to simplify the suburban villa and, much as Wright and the Greenes were doing in this country, to bring it in closer sympathy with the ground and to raise the spirit of domestic life by giving homes a sculptural and ornamental program that had the same aspirations as a work of art. Homes now became places in which to enjoy the everyday rather than sites of ceremony and entertainment, and – as Mimi Zeiger shows – the aesthetics of an extravaganza like the Gamble or Blacker house could be readily translated to more modest homes in a way that the pomp of a Beaux Arts mansion could not. Perhaps the greatest step in making us modern is this: that we might all live in ways that whatever the scale and cost would look roughly alike.There were many models for these experiments: the traditional Japanese house that was so important to the Pasadena school, the relaxed plan of the ‘English house’ emerging in the late Victorian era that so caught the imagination of the Germans, or the rural vernacular around them. In some ways the door to the modern home was opened by the adoption of exotic models, especially the looser domestic landscape of the Mediterranean and Arab lands that was making its way west to California. With its plate glass windows and Moorish decoration, Eckel and Mann’s adventurous example of a magnate’s villa in the Midwest (the territory from which the Greene brothers and their clients came) draws on Moorish traditions to propose something with none of the pretensions of European grandeur that the barons of Newport and Fifth Avenue demanded of their homes.

The next great burst of invention we look at comes from 1935 to 1940, as the Depression years eased and the automobile became part of our way of life. Building on isolated housing experiments of the 1920s – we can think of Schindler’s King’s Road House in Los Angeles, or Neutra’s Lovell Health House – and often focusing on the moderate cost home, architects laid out a feast of new ideas for domestic architecture that proved to be the groundwork for the modern home of the postwar years. Some of the great examples – like Neutra’s Von Sternberg house, built in thin gauge steel – have gone. Some, like Frank Lloyd Wright’s All-Steel community for LA’s Baldwin Hills, never got off the ground. Others were only developed as models – here is Ernest Born and Thomas Church’s staggeringly original proposition for a new kind of small house and garden on a city lot, in which a tapered mezzanine begins life as a kitchen, and a dining room begins indoors and ends up as a garden bridge, and one entire high wall is glass. More, like the German Expressionist Herman Finsterlin’s home (conceived as a cave or primitive animal in which shelter becomes a fluid, emotional or even tactile experience), were put forward simply as provocations and possibilities.

Two very real examples find new ways to deal with site. We are constantly rediscovering the great Swedish architect Gunnar Asplund, whose work, like Wright’s but with less flamboyance, both embraces conventions and defies them with his own unorthodox originality. Here we see his summer home, neither modern nortraditional, built on an island near Stockholm, as he draws it stepping quietly but asymmetrically down the slope of its hill, using a cliff as shelter, and finding its proportions in the landscape. High in the Malibu hills, Wright’s transcendent ‘Eaglefeather’ for Arch Oboler (on which Lautner worked) takes a nearly identical topography in a much grander setting and thrusts itself boldly out from it so that, like Silvertop, it soars above the ground to make the vistas and skies around it sing. One experiments by deferring to its surroundings, the other by asserting itself to heighten their effect.

Our third moment starts as the rational and functional conventions of postwar modernism begin to give way – at the time of Silvertop and the Kambara house – first to the idea that the house could exploit new structural systems (as at Silvertop) or to a new approach to light and site to establish the house as an emotive or transcendent space (as at Kambara). We see Le Corbusier using the roof of the first ‘Unite d’Habitation’ as a safely-enclosed community nursery, where children will explore the shapes and shadows of architecture and the distances beyond it. Lautner, in an unbuilt project for the artist Edgar Ewing, explores different ways – both radical – to raise the house above a steep hillside to blend shelter and vista. The French-Hungarian Antti Lovag proposes the home as an interlocking set of bubbles of varied size that serve as “space both for encounter and reflection”, taking advantage of new materials that would make sculpted space a reality where Finsterlin could only imagine it.

The last of these projects moves us a short step forward to a single year, 1972, with three projects that questioned some of the basic premises of the house. In John Hejduk’s wall houses, he simply builds his own hillside, hanging the dwellings like bubbles on the side of a constructed escarpment. His Bye House, proposed for a client for a site in Connecticut and built thirty years later in the Netherlands, develops the idea for a single dwelling suspending the living space from a huge wall, bringing you into it through a long tunnel that makes the vista explode before you when you get there. Much has been written about Peter Eisenman’s House 6, in which he follows a geometric procedure to shape a perfectly agreeable weekend dwelling by bisecting a cube to find its separations and divisions – walls, floors and openings, all determined by slicing through a hypothetical box. But it seems to me that the most important as an assertion of the independence and self-containment of the house is that it stands on its pad amidst a flat swath of greenery as a piece of sculpture sits in a garden, charging the space around it. Ugo La Pietra’s prescient ‘housing cell,’ built for an exhibition at MoMA that year, suggests that in an electronic universe, the only home or space we need might be a sort of tent into which all the necessities and experience of the world around us can be brought by telephone. If he was right, then we don’t need houses at all.

LOSS AND RECOVERY

Architects have long memories, and experiments like these remain subjects for analysis in the design studios of schools and are continually revisited in the literature. So forty years later we see the molded shapes of the Expressionist house coming back in the fluid forms of Lautner, Lovag and Hejduk, or the early Modernist geometries of white cubes and straight lines being re-examined in their different fashion by Eisenman and Neutra.The first ventures into the ‘post-Modern’ looked back across an even longer history, reinventing the house with familiar building blocks – like the column and the arched window that architects through the ages would recognize – then assembling, simplifying and coloring them in quite unexpected proportions and relationships. In Michael Graves’ house for Aspen, we can hear echoes of many earlier experiments in this portfolio: the modernized exoticism of that 1880s house in Missouri; the restrained luxury of those villas from turn of the century Vienna; and the subtle twists on conventional scale, placement and symmetry that marks Asplund’s summer house. Graves uses classical columns, but they tower above the house rather than support it. A traditional pergola sits on the roof rather than the ground, and of two identical half-moon windows from the Renaissance, one of them is placed in the center of its wall and the other buts abruptly against a corner.

It takes great determination, an exceptional client and heroic patience to see any innovative house move from ideas on paper to a building on the ground.Wright’s Eaglefeather was never finished. John Hejduk never lived to see one of his wall houses rise. Lautner never got to build his experiments in hillside living for the Ewings and had to wait until the Chemosphere to bring its ideas to fruition.The story of Silvertop is one of immense struggle, and John Hejduk never lived to see one of his wall houses rise.Yet the rare examples that make it – even those we know the best – are always and increasingly in danger. Experimenting with the application of industrially made components to a domestic landscape, it took the Eames more than five years to move their Case Study home and studio from a first design in 1945 to realization.

Among iconic experiments in living, we mourn the loss of Irving Gill’s Dodge House in Hollywood and the demolition of Schindler’s Wolfe complex on Catalina, John Johansen’s Labyrinth house, and Arthur Erickson’s pioneering Graham house in Vancouver. Other signal laboratory houses of our time – Eisenman’s House 6 in Connecticut, Steven Holl’s Stretto House in Dallas, and Robert Venturi’s mother’s house, to name only three – have recently changed hands for the first time. Others – like Wright’s prototype of ‘How to Live in the Southwest’ for his son David – have been saved from the developer’s wrecking ball by the bell. Others – like Harwell Harris’ Havens House and Schindler’s Freeman – languish in the care of universities. Even more fall victim to ‘mid-century modernisation’. I have stood in too many once great houses whose moments of excitement have been swallowed up in a sort of off-the-shelf affection for a style rather than honored with an attempt to discern and respect what made the buildings adventurous or lent them drama. And once degraded – like Neutra’s Kaufmann desert house – it takes vast resources and a heroic commitment to bring them back to life.

Yet not every house by even a great architect is a great adventure. We must acknowledge different levels of preservation, on a long scale, from the almost archeological approach that Escher Gunewardena are rightly taking at the Eames home and studio, to the subtle refinements and enlightening the same team have made to a Quincy Jones house whose good bones are made better by their intervention. In this magazine we have instances of all extremes – a Neutra in such an undisturbed state of preservation that its new owners will surely gain more delight from curating their living space than adapting it; a never quite completed as intended Lautner of such stunning importance and livability that it warrants as much fidelity to the de- signer’s intent as its new owners can muster; and a Greene and Greene that, generous toward change from the start, is forgiving and resilient enough to repay its next owners handsomely so long as the spirit of the place and the time in which it was made is kept intact.