The John A. Smith House

La Habra Heights, California

by Jocelyn Gibbs

Cliff May (1908-1989), the designer and builder famous for popularizing the California ranch house, insisted that he “built just one kind of house, had just one style.” The persistence of his vision of what a house should be and how people should live, came from his pride in his family’s California heritage —he was related to most of the land grant families of San Diego County—and from his memories of childhood summers spent on a ranch run by his aunt. The rambling wood and adobe buildings of Jane Magee’s ranch and the indoor-outdoor life there instilled in May a life-long belief that the best way to live was in a ranch house, close to the ground, especially in the beneficent landscape and climate of California. beneficent landscape and climate of California.

When May first began designing and building houses in San Diego during the late 1920s, he was fortunate to attract mentors, from among San Diego developers, who helped him get started. May wasn’t trained as an architect but he knew what he liked. He borrowed details for his charming San Diego houses from existing adobe structures, ranch buildings, and from the Spanish Colonial style so popular throughout Southern California in the 1920s.

By the early 1930s May had attracted the attention of businessman John Arnholt Smith, who, after visiting several of May’s speculative houses in San Diego, became his most important mentor and business partner. May later acknowledged that Smith had been like a second father. Smith, a San Diego financier who was buying up land and oil wells in Los Angeles, convinced May that the city to the north offered more opportunities for development than San Diego. According to May, Smith told him, “You should get out of San Diego because there will never be any oil there. If you don’t have oil, you don’t have banking, and without banking, why, you’re not going to have a very big city.” Their first project together, and May’s first design beyond the San Diego area, was, as stated on the specifications, a “hacienda for Mr. and Mrs. John A. Smith” built in 1934-1936 on forty acres at the northern edge of Orange County, in the Los Angeles suburb of La Habra.

Smith and May used this house as an advertisement for the possibilities of their new partnership. It was the first of the luxury ranch houses that May would design with Smith’s backing, most of them in Los Angeles. They opened the Smith house to the public for several weeks after it was completed and articles and photographs describing the house appeared in local and national magazines, including Architectural Digest, Architectural Forum, and Sunset Western Ranch House through the mid-1940s.

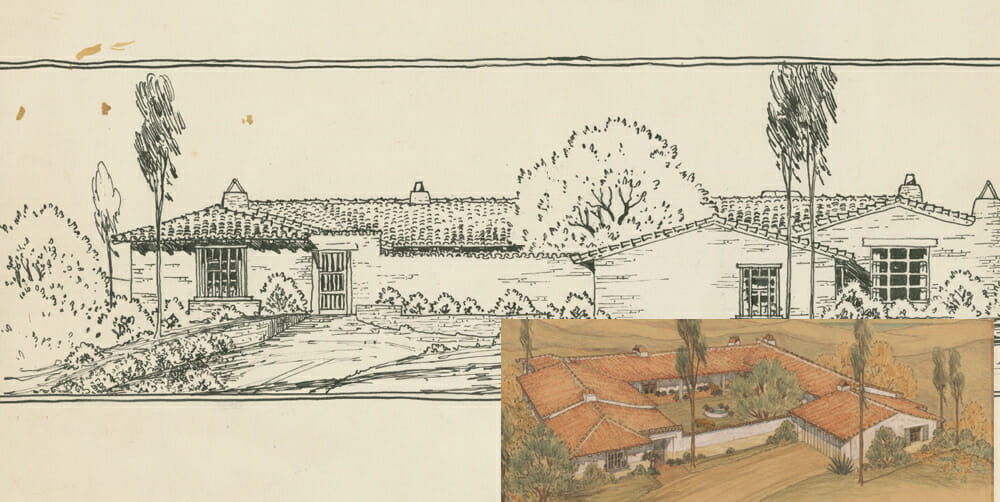

Photographs and drawings from May’s archive in the Art, Design & Architecture Museum, UC Santa Barbara, show the house and land as they looked in 1936. A large gatehouse, with tiled roof and heavy wood doors marks the entrance to the property. An unpaved, curving drive arrived at the top of the small hill to the house and attached garage. May often said that his houses didn’t have fronts or backs, but his entrance facades always had few openings in order to preserve the privacy of the interior. He always opened other parts of the house to interior courts, the garden landscape, or distant views. The entrance façade of the Smith house, with its whitewashed rough brick walls, red tile roof, and single window covered with a wooden grill, evokes the flavor of the early 19th century, when La Habra was the Spanish land grant property, Rancho Cañada de La Habra. When a drawing of the house appeared in Sunset Western Ranch Houses in 1946, the editors added the caption, “Its heritage is unmistakable.”

As in nearly all of Cliff May’s hacienda style ranch houses, the entrance leads, not to the interior of the house, but to a corridor that opens on one side to an enclosed patio and leads to the interior door to the house.

On the other side of the corridor are two guest bedrooms with two bathrooms between them. The covered and tiled corridor and the tiled octagonal patio fountain would have provided cool relief from the dusty drive and dry, hot climate of the surrounding agricultural lands. The roof profile is low around the edge of the patio, providing shade and a view of the highly textured effect of the randomly laid roof tiles. The patio is the center of the house, which surrounds it on three sides. This plan, which May used several times, is very similar to that of the Estudillo house, the historic adobe in San Diego, built by May’s ancestor José Maria Estudillo in 1827.

May was a designer of scenes and a master at creating romantic effects. He evoked the past with rusticated details and by highlighting the primary nature of his materials: bricks, tiles, stucco and wood. Once inside the house proper, the corridor turns the corner to the most enchanting space in the house. The loggia is both a hallway and an informal living room. The dining room, kitchen, and living room each open onto the loggia, which connects on the other side of its length to the patio through a wall of glass windows and doors. Tucked off on the side of the loggia is a corner fireplace in the rounded shape of an adobe kiva. Photographs from the 1930s show that the Smiths furnished the loggia with informal and comfortable rattan chairs and tables. One can imagine family members, staff, ranch hands, and visitors moving through this lovely space, meeting, resting, and enjoying the view to the patio.

May placed the dining room and the living room into the corners at the base of the Ushaped plan. To take advantage of the spectacular site, he swiveled both of these rooms so that they extend out toward the view and the hills in the distance. The dining room ceiling is full of heavy, rough wooden beams that outline the run and gentle slope of the roof. In vintage photographs the dining furniture, which remains in the house today, is rustic, made of dark wood, and reminiscent of the Monterey Mission style furniture that May saw in Barker Brothers furniture store in San Diego and copied for his first house in 1931. The fabric of the curtains evokes the patterns of serapes. Between the dining room and kitchen is an irregularly shaped breakfast room. May liked, and mimicked, irregular surfaces, colliding rooflines, and irregularshaped rooms because it reminded him of the roughly made rambling structures of old California, with additions made willy-nilly over the years as needed. On other projects May famously tore down walls that were too straight or smooth, urging his workmen to make them more primitively.

The living room in the Smith house is grand. According to the drawings in the archive, it is more than twice as long as it is wide, measuring approximately 28 feet long by 17 feet wide. The shape and position of the room dramatically emphasizes the view through the large window opposite the living room entrance.

A fireplace in the middle of one side of the room is the social focus of the room and the largest of the four fireplaces in the house. The loggia ends outside the living room at the beginning of the private wing of the house. This arm of the Ushaped plan holds a library, bath, and master bedroom.

The master bedroom opens directly onto the patio. The site is one of the distinctive features of the house, still impressive though it has shrunk over the years. The house has had only four owners to date, but during that time most of Smith’s original forty acres were sold off as La Habra developed and the area around the house become suburban. Smith sold the house and its remaining land to William Clum who lived in the house for 10 years. Clum was probably related to John P. Clum, an agent in the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, former mayor of Tombstone, friend of Wyatt Earp, and the man who reportedly captured the prominent Apache leader, Geronimo. Former friends and family members have recounted the story that Geronimo’s gun was kept over the mantle in the house when Clum lived there. The current owners purchased the house from the widow of the businessman and banker, Robert Lynch, who owned the house for more than forty years. Lynch and his widow further reduced the size of the property from 23 acres to the present approximately 2.5 acres.

The house today still evokes the romance of May’s original design. The texture of the materials, the flow of the rooms around the patio and loggia, and the distant hills remain. There have been changes over the years. A swimming pool was added in the mid-1940s. Cliff May remodeled the house slightly for Clum in 1953. The aviary, part of May’s original design remains today, though filled with plants instead of birds. The original garage is now an informal living room/playroom and new garages sit at the bottom of the property near the gatehouse. What was once driveway all the up to the house is now part of a manicured garden. Nevertheless, this house remains one of Cliff May’s most important designs.

In 1935 May moved to Los Angeles where his partnership with Smith continued through the end of the 1940s. With Smith’s financial backing and May’s designs, they built and quickly sold a large speculative ranch house on Stone Canyon Road in Los Angeles, several houses nearby in Sullivan Canyon, and then, beginning in 1938, the astonishing Riviera Ranch, a development, complete with riding trails and stables, of luxury California ranch houses in Brentwood.

Under the influence of magazine editors, May’s later designs were more sophisticated and sleeker— modern interpretations of the California ranch house—culminating in Mandalay, the 6,000 square foot house he built for himself, beginning in 1956, at the top of Sullivan Canyon, just outside the Riviera Ranch. The California ranch house made Cliff May famous. He built houses around the country and in other parts of the world but stayed in the Sullivan Canyon area for the rest of his life. He died at his office in Riviera Ranch in 1989. The romance of the California ranch house continues to have great appeal.

Many of May’s designs remain and are lovingly cared for in Santa Barbara, San Diego, Los Angeles, Malibu, Brentwood, Camarillo, and in the City of Lakewood where the largest tract of low-cost ranch houses, Lakewood Rancho Estates, designed by May and his partner Christian Choate, was built by the developer Ross Cortese, between 1953 and 1955. Cliff May believed that everyone should live in a ranch house.