Modernism on the Ranch

In conversation with Mark Morrison, architect Phillip Jon Brown recounts the challenges he faced in 1984: designing an elegant and surprising two-story modernist residence on Errol Flynn’s former ranch, a parcel of land as wild as its former owner’s social life.

by Mark Morrison

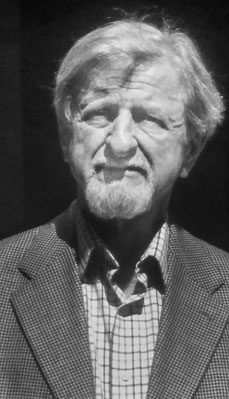

In 1984, Philip Brown was an emerging USC-trained architect and urban planner who had only designed six houses—two of which were for his family members. Yet, in this still-forming stage of his career, he was offered a meaningful—and challenging—opportunity: To design a modernist two-story house on a wild parcel of land in the Hollywood Hills, one lot of four carved from a former ranch that once belonged to the Golden Age of Hollywood actor Errol Flynn. Developers asked Brown to work within the confines and demands of a restrictive budget, a tight timeframe, sloping land and new energy regulations. In response, the architect set about creating a residence designed for resale that would appeal to a spectrum of prospective buyers and yet offer qualities that made the house feel rare and distinct. The result is the 7740 Flynn Ranch Road house: a 5,700-square-foot abode that, although constructed from simple materials, is nuanced and elegant, with sculptural contours that are surprising and carefully rendered.

In 2018, 7740 Flynn Ranch Road was put up for sale for the third time in 34 years. Brown took the opportunity to visit the house again. He moved from floor to floor, from outside to in, taking in the views he had engineered, the original details that had lasted three decades, as well as the thoughtful improvements each owner had made.

Screenwriter Hadley Davis Rierson, who, along with her husband, television executive Lee Rierson, purchased the house in January 2019, says she was captivated by the house’s artistry, even before she entered the property. The double-width front door, she recalls, swung open in a “sublime” way, and that made her instantly intrigued about what lay inside. However, she added, “It was the banister leading to the second floor that really got me. Like the door, the banister was shaped with an elegant simplicity. I began climbing up the stairs, put my hand down and found the banister fit perfectly in my palm. That was the feeling—the house fit us. It’s not just beautifully designed to look at. It’s beautifully designed to live in.”

After his visit to 7740 Flynn Ranch Road, Brown looked back on his design with much fondness and an appreciation for the careful guardianship of its two—now three—owners. “You know, it’s come through [the years] very nicely,” he said, taking in the afternoon light as it streamed into the living room. Brown spoke with architectural writer and ArchitectureforSale, Quarterly associate editor Mark Morrison about his process designing the house. (Morrison died of leukemia in December 2019, before he could finish this story. Four months after his passing, Morrison’s longtime Time Inc. colleague and friend, journalist Alison Singh Gee, helped him complete the interview with Brown.) The following Q & A between the architect and the writer reveals the enduring intelligence and creativity of Brown’s design and Morrison’s deep appreciation for the integrity, innovation and beauty of inspired architecture.

MARK MORRISON, ARCHITECTUREFORSALE, QUARTERLY:

Tell me about what the land here was like when you were first asked to design this house.

PHIL BROWN:

It was kind of a toy ranch, a small three-acre ranch, with some animals and maybe a barn. There was natural vegetation that was eventually cleared off. The animals—horses and goats—ate it. The next-door neighbor down below in Nichols Canyon had tiki gods that spit water on his property. He was a trip. You have to read My Wicked, Wicked Ways (Errol Flynn’s 1959 autobiography) to really understand the history of this area. This is a magic spot.

The lot came with a slope. Adding to that challenge was that during this era, we had to work with the building code, Title 24, which limited the amount of glass you could incorporate into your design. To stay within those limitations, we closed off pretty much the entire north side of the house. This south side of the house was opened up, so you could get a nice sunlit living room.

The steel influence [pointing to steel frames around the house, a steel column in the dining room, and louvers that hang above the expansive living room window] was part of the whole vision. I was kind of following that as a major influence. It suggested rectilinear forms. What changed the design of the house from a tight box was that I had separated the rectilinear form to develop that diagonal access. That opened things out to a lot of complexity in views. Not only the rectilinear or orthogonal views but the diagonal views. I think that’s what is so astonishing about the house.

I was also very conscious of scale. That’s why we don’t have the verticality in the living room. It’s a horizontal line.

AFSQ: And yet you have the vertical fireplace to balance it. And that’s what I notice—there’s a balance between verticals and horizontals throughout the whole house.

How did you come up with the idea for the louvers?

PB: I came up with the louvers to satisfy the Title 24 requirements. They are for shading; they cut down the coefficients. The code regulated that you could only use 20 percent of the floor space as glass. Title 24 came into place in the 1970s—either 1974 or 1975—when the energy crisis hit. Title 24 forced out a lot of architects who were working with glass—for example is Buff and Hensman, who created great glass houses.

AFSQ: When you look at them with an uneducated eye, the louvers looks like a decorative embellishment. They’re aesthetically pleasing.

PB: The louvers allow winter sun to come directly in. When the earth levels through the seasons, the louvers then cut out the summer rays.

AFSQ: How much studying did you have to do to do this?

PB: We worked with a professor at U.S.C., Ralph Morris. He was the sun man. He had all his approaches to design. He was a self-taught scientist.

AFSQ: It looks like in the building of this house you faced nonstop challenges. Everywhere you turn, it’s something else. You have all this legally required stuff and you just made it beautiful. Look at these elevations! Every elevation of the house is sculpture. There’s no ugly bad side.

The three garages for the house, each one is set back from the other. You could have just done them all the same, right? Meaning you could have built them in one solid line.

PB: Yes, but that would have hurt the verticality of this seam of the house.

AFSQ: And that would have added more of a sense of bulk, wouldn’t it, as opposed to this sculptural effect. Executed by someone else, these garages might have been done sloppily. But you did it with an eye on design and sculpture. What this house is reflective of is that every room, or even every corner, offers a different experience.

What was your inspiration for the house?

PB: That’s an unusual question in a sense. The way I work is more of a “what is the problem here and how do I solve it?” approach. So it’s not a sunset or a big tree that’s my inspiration.

The problem was that in building a house designed for resale, you don’t know who’s going to buy it. So you make something as appealing as you can for a general buyer. And then, you get into the more technical aspects of the site, including structure, cost per square foot and so on.

Instead of designing with the pursuits and goals of a particular buyer I had to design a house that was appealing to a general buyer’s sensibility, and one that would be appealing to me as well. It had to be a somewhat conservative house, conservative in that it was going to be rectilinear and straightforward, not like the John Lautner house. But I still wanted it to be elegant.

My preference in terms of architecture is space and light. That is an orientation that I have and that is what’s appealing to me. These qualities influence the house quite a bit.

The site itself is a very strong contributor to how it is designed. A sloping site led to a three-story structure. It wasn’t a radically sloping site, but just enough to affect layout determinants. I knew I would place the three-car garage was at one level, and then the majority of living space would be above that. The entertainment area would be outside and the bedrooms would be upstairs. I wanted it to be a very flowing space.

The entire Flynn Ranch property was a four-parcel map. It was one big lot that we divided into four parcels, including making the road. I designed Lot A, on which 7740 Flynn Ranch Road sits, from that parcel.

AFSQ: You did the drawings for the house yourself. How did the design evolve from there?

PB: Well, I’ve been thinking about what it is that I did in regards to that property. So much of design is intuitive. One develops an approach to going about solving the design. Over time it becomes a deeply imbedded process. That is because there are so many influences and systems that are brought into balance in a design. And, I would say that the design grows out of a design process rather than is imposed upon it from the outside, as with a preconceived style for example.

One thing to recognize is the drawing process itself. Overlays of paper are made of subjects one upon another, where drawings are made to see through the thin overlaid paper to search out possible relationships of those drawings. There are internal functional relationships of activities, the necessary structural resolution of the building so it stands the test of time, and earthquakes. There is also the siting that is made to take advantage of—again, functional relationships the site requires and of subjects like views and sunlight. In return, these elements offer complementing relationships to internal functions.

But wait, I’m just getting started. The overlays of paper allow a coalescing of subjects into a form, so that older searches can be tossed aside. They have been superseded by the more unified form to which are then overlaid again with further searches of new influencing subjects on new drawings on top of that. Over and over again the search and the growth of the design will then emerge. Is it good enough? It may not be. So then further searching and coalescing takes place.

Over the years one becomes familiar with how the design emerges from the relationships of influence. One sees opportunities to emphasize in order to bring out the spirit in the design. 7740 Flynn Ranch Road allowed southern light to be emphasized. It also allowed a complexity of internal and external spatial relationships to take place in a three-dimensional contrasting experience while moving through and being in the spaces. The living room is horizontal, light filled and indoor-outdoor related. A diagonal axis relates it to the dining room which is a vertical volume overlooking vertical tree foliage through vertical fenestration to views beyond.

Between the horizontal steel elements of the living room and the vertical fenestration in the dining room is a two-story-tall exclamation point of a steel column, which in the dining room soars to the ceiling. However, in the living room this same column is seen as a horizontal fitting in with the relaxed formalism of that large space. So moving through horizontal and vertical space as well on the diagonal makes a three dimensional rather than a flat experience of orienting to walls and spaces orthogonally. It has made a difference in the feel of the house. And the open bridge from the stair well over to the master bedroom allows the experience of these contrasting spaces once again but from the high vantage point of the upper story.

AFSQ: There is a lot of understated genius going on in this house. In your opinion, which of these many design elements make this home unique?

PB: I would say that the complexity of the space with the X, Y and Z axis spatial experience makes a unique experience in the home. The sun screen is another horizontal element in the living room. But more than that, it is a light sculpture. It is not only working through the day but also through the year as the sun arcs over the house each day and also through the year as the earth wobbles in its annual course around the sun.

AFSQ: So, do you think 7740 Flynn Ranch Road represents a particular style of yours that you can put into words or name? Have you ever tried to name your style?

PB: No, as I say, it’s sort of derived from steel, which is kind of a reasoned architecture.

AFSQ: Would you say this house is representative of you, though? Of your work in general?

PB: Oh, yes. Oh, sure.

AFSQ: Because it’s a design for resale house, obviously, it was purely you. You didn’t do it to please anybody.

PB: That’s right. (Laughs).

AFSQ: So would you say this is then the most reflective of your work? Of you?

PB: Um, maybe today. You know, it’s one that hasn’t been impinged upon—that it’s come through very nicely.

AFSQ: How do you feel now when you return? When you look at it now?

PB: It has remained very nice. The owners mostly kept things they way they were. They didn’t violate the idea of the house. In fact, they made some improvements. For example, originally the house had a sand finish, and it was gradated with color as well. It was a warm sandstone color at the bottom, working up to a white. That was a rustication sensibility. Now the the exterior stucco is a smooth finish. It is smooth coated and more of a grayish color.

AFSQ: How would you like to be remembered?

PB: As an urban planner. I got a degree in urban design and I am still going at it. I got the degree because I felt it was more relevant than design, that it had more social impact. Designing houses for rich people has, over all, not been that rewarding. For example, I designed a house for Dick Clark, who seemed menacing. I had to struggle with that as an architect designing for other people.

However, I did design my own house in Benedict Canyon. Working with a subcontractor, I basically built the house with my own two hands. I did all the framing and roofing. This happened during the early 1990s, during the recession, and I didn’t have any clients anyway. Building my own house has allowed me to have a work place and a home. It has been affordable. It has kept me in a free state of thinking for myself and developing my own career, instead of having to work for somebody else.

Contact us about this property:

Error: Contact form not found.