Harwell Hamilton Harris, FAIA

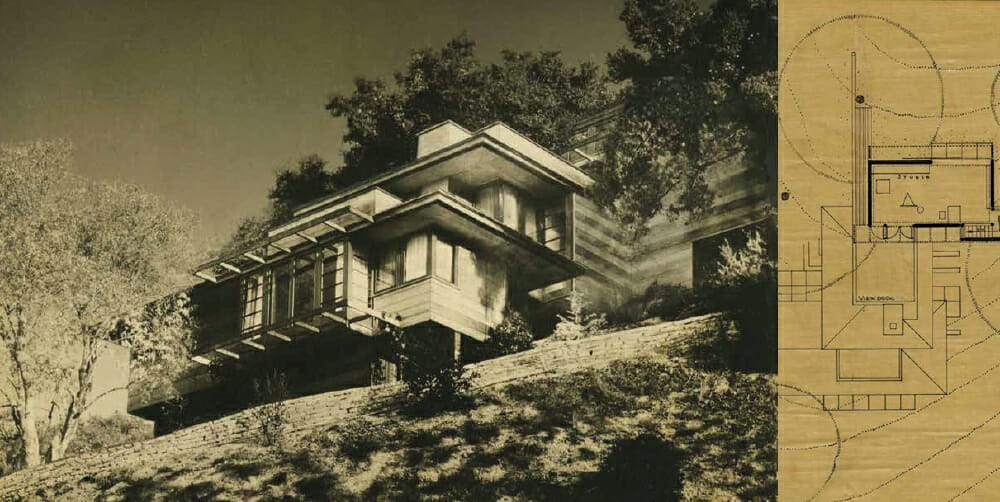

Mary and Lee Blair House, 1939

by Alan Hess

Current Photographs by Cameron Carothers unless otherwise noted

The ultimate emblem of America’s mid-twentieth century love affair with modernism may not be the iconic 1949 Eames fiberglass chair or the indoor-outdoor Eichler tract houses of the early 1950s. It was arguably Walt Disney Studio’s adoption of a stylized modern aesthetic in its popular animated movies Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951) and Peter Pan (1953) — a far cry from the traditional Old World fairy tale look of Snow White and Pinocchio in the 1930s. And it was a female artist – Mary Blair (1911-1978)—who helped Walt Disney plot that new direction. So, fittingly, the 1939 house that noted Los Angeles architect Harwell Hamilton Harris (1903-1990) designed for Mary and her husband Lee (1911-1993) is equally significant.

The Blairs were not only modern artists, they lived modern at a time when the modernist movement in Southern California was at its most fertile and prolific. Mary’s watercolor, gouache or collage paintings defined the mood and look of Disney’s new films with stylized shapes, biomorphic forms and bold fields of vibrant color that were drawn from the era’s modern art forms, from cubism to surrealism. Her confident, colorful compositions rank with the work of modern graphic designers like Alexander Girard, Alvin Lustig and Ray Eames, and they seem to anticipate David Hockney. “Walt said that I knew about colors he had never heard of before,” Mary once said. At a time when women in the animation industry were mostly relegated to inking cells at low wages, she was one of Walt Disney’s favorite artists.

The house Harris designed for the Blairs embodied that emerging spirit of modernism in California. Tucked on a small hillside street overlooking the San Fernando Valley near Cahuenga Pass, the design was at the frontier of modern architecture when Rudolph Schindler, John Lautner, Gregory Ain and Richard Neutra (Harris’ former boss) were taking modern architecture in newcreative directions beyond the International Style. But over the years, the house had been added to, original windows removed, and new coats of paint added—until it was restored to virtually original condition by designer David Brudnicki.

Brudnicki and his team quickly realized the high quality of Harris’ original design and committed themselves to honoring his architectural concept and the results do justice to an excellent design. Some decisions were easier; scraping away layers of paint or peering behind hinges, they were able to determine the original soft gray-green color of the wood trim. The living room’s original wood and glass doors had been replaced, but with repairs most of them could still be used — even though they had been stored outside for fifty years!

In other cases, the original details were not as easy to determine, but Brudnicki reports that the design itself helped them. Harris used a regular module for the structure, so Brudnicki and his contractor Ray Wright could follow the logic of the structure in returning the house to its original state. Wright kept a close lookout for original construction details, such as the pattern of nails (not glue) on paneling, or the use of mitered corners. Restoration plumber Ryan Soniat went outof his way to find the original American Standard handles for the bathroom fixtures, and replated an original nickel light fixture. Brudnicki discovered another way to confirm their decisions: They found that when anything non-original was taken off, the house just looked better.

One historic detail they could confirm: Lee Blair helped build the house himself. Behind walls they found written notes that said “Mr. Blair hammer here” to guide him. With an architect of Harris’ caliber, there was always a reason for each detail of the plan. His creative genius at this early point in his career can now be fully appreciated. Though the house was published in Architectural Forum and House Beautiful when new, it is not widely known. Likewise, Harris is also not as widely known as he deserves to be. Restored, the Blair house shows off the rich range of sources and ideas the architect drew upon, and his own creativity in pushing those ideas to new places.

Harris had two huge advantages in becoming a modern architect in California. First, he is a native, born in the rich agricultural town of Redlands and he understood the region’s climate, landscape, and its forward-thinking people. Second, his first job as an architect (he had studied sculpture at L.A.’s seminal Chouinard Institute of Art) was in the office of Richard Neutra, possibly the best place to learn about modern architecture at a time when the architecture schools were still teaching Beaux Arts Classicism. In his own work, Harris quickly melded his knowledge of the place and culture with his knowledge of new materials and forms. The Blair house is convincing evidence.

The Blairs were a working couple whose clients included various animation studios and advertising agencies. And when possible, they devoted time to their real love—their own fine art painting. Both were part of the California School of painting which included figures such as Phil Dike, Millard Sheets, and Charles Payzant. So the one-bedroom house Harris designed for them was a perfect fit for their simple lifestyle. And the steep hillside site the house was built on helped determine its design as much as anything else. Too steep to carve out a flat building pad, the site caused Harris to stack the three levels one atop the other, taking advantage of the spatial play suggested by this arrangement. The first floor was for entertaining friends; it featured the living room, dining area and kitchen. The zig-zagging staircase leads to the one bedroom and bathroom.

Another set of stairs leads to a spacious studio. Each level has its own private outdoor space. Harris crafted each floor – and its distinct function – to take advantage of the light, ventilation, expansive views of the San Fernando Valley, and easy access to the wooded hillside. Though the house is not large, Harris makes the space functional and flexible with built-in furniture and movable wall dividers.

A later owner added a mechanized funicular to get from the street-level garage up to the front door, but the Blairs used a switchback path up the hill. Twin front doors are made of ribbed glass,so that even before entering, visitors can see the natural light, filtered through the trees, that fills the house. The living room and dining area are one space – but this is not the undefined “universal space” of Mies van der Rohe’s version of modernism. Harris mixes window walls with solid walls clad in unpainted plywood as well as built-in furniture to maximize the use of the space. To the left, the brick fireplace is an abstract sculpture in itself. A built-in couch and side table next to it create a corner that feels safe and cozy. To one side, a floor-to-ceiling glass bay, cantilevered over the hillside, expands the view out to the canyon. On the other side is another wall of glass that looks out to an intimate but spacious patio and the wooded hillside beyond. This glass wall unites the living/entertaining area into a single indoor-outdoor room.

Harris’ subtle and logical decorative touches should also be noted: The movable French doors frame a solid piece of glass, while the fixed frames at the corners are divided into five horizontal panels to create a lively contrasting rhythm. At the other end of the living room, two solid walls clad in unpainted plywood panels define the dining area. Depending on how informal the hosts want to be, the kitchen beyond can be left open to view or shut off with a large two-panel folding door that matches the plywood, creating a seamless wood wall. The space is not large, but there is no sense of being cramped. Well-trained in modern principles, Harris makes the space itself the architecture; the walls and ceilings subtly shape it. The architect absorbed the lessons of his friend Frank Lloyd Wright: windows always turn the corner to break the boxy feel of traditional architecture; glass walls extend the living space to the outside; the ceiling height rises or lowers to suggest expansiveness or intimacy; a dropped soffit over the built-in sofa increases its intimate feel and hides indirect lighting (a relatively new idea in 1939) to reflect softly off the white Celotex ceiling (also a new product).

Harris clearly grasped the logical aspect of modernism. The house is a complex of many interlocking systems: Structure, walls, mechanical systems, openings for ventilation, sources of light (both natural and artificial), and so on. Like Rudolph Schindler (another Southern California architect and European ex-pat he knew and admired), Harris’ design draws its art from revealing that complexity, rather than disguising it behind a false simplicity. So the structure is exposed in the four-by-four wood posts along the glass walls and embedded in the solid walls. He celebrates them throughout the house by painting them gray-green to contrast with the light-toned walls and then emphasizing them with a delicate decorative reveal of thin wood moldings.

Compact stairs lead from the entry vestibule to the master bedroom. The visitor may not notice it at first, but a high window floods the stair with natural light from the side. It washes the walls to pick up different tints in the paint color and gradations in the shadows. As artists, the Blairs must have appreciated the ever-changing light. The house is a three dimensional work of art.

The master bedroom repeats the themes of the living room, but reconfigured for privacy. Built-in furniture has the efficiency of a ship’s stateroom. The roof of the lower floor becomes a private deck looking out to the view – while glass French doors let you step directly out onto the hill on the other side. Up one more flight of steps is the spacious studio where Mary Blair worked at her drafting table, with a built-in counter for supply drawers and a sink. A sloped ceiling catches northern light from the high clerestory windows and reflects it evenly through the room – the room is a machine for painting in. Like the other floors, a deck allowed Mary and Lee to enjoy the panoramic view of the Valley on one side. On the other side, a twelve-foot-long glass door slides completely off its opening to invite them to step outside onto the wooded knoll.

It was in this studio that Mary created many of her designs between 1939 and the mid – 1940s. Many were influenced by the 1941 South American excursion lead by Walt and Lillian Disney for the Blairs and several other studio artists. The native folk art and brilliant colors Mary discovered there became a major influence on her artwork. And even the intrusion of World War II didn’t disrupt her work—though it changed her base of operations.

During the war, Lee was stationed near Washington, D.C., and after, he established himself in New York as a TV commercial and industrial film producer. The couple moved from their hillside home by Harris to a house (also modern) in the Long Island suburb of Great Neck. Their two children arrived in 1946 and 1950, but Mary remained a career woman ahead of her times, commuting by plane to Burbank to work on different projects for Disney through the years. She also worked with advertising agencies in New York, wrote children’s books, and designed the sets for a Duke Ellington mini-opera at Radio City Music Hall. Walt Disney always kept a lookout for projects suited to Mary’s talents; of these, her best known is undoubtedly the design for the Pepsi-Cola and UNICEF pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. It proved so popular that Uncle Walt moved the whole ride featuring hundreds of international doll-like children back to Disneyland where it became universally known as “It’s a Small World.”

Today, the restored Blair house reminds us of the extraordinary range of creative design that Southern California generated in the mid twentieth century. Harwell Harris was part of it, and well aware of other architects’ work. The Blair house’s wide overhangs and horizontal redwood boards with thin battens echo Frank Lloyd Wright. The contrast of large transparent walls with opaque walls defining specific functions (like the dining area) reflect the geometries of Neutra houses. The design’s intricate three – dimensional interlocking of space, structure, form and function recall Schindler’s originality. Going back to an even earlier period, the house’s thoughtful redwood construction acknowledges the Craftsman designs of Charles and Henry Greene at a time when the brothers from Pasadena had been mostly forgotten; it was Harris’ wife Jean Murray Bangs who rediscovered their work and brought their contributions back to the attention of the architectural community – and Harris.

The design, however, is unmistakably Harris’ own creative vision. The similarities simply remind us of the fertility of the region’s rapidly evolving architecture. Harris and his colleagues all responded to key aspects of Southern California: the benign climate, the hillside sites, the panoramic views, the casual lifestyle that drew people there. He understood Californians’ lack of pretension and used natural, newly invented, and inexpensive materials like plywood, Celotex, woven grass carpets, and grass cloth fabric on sliding doors (echoing Harris’ interest in Japanese architecture) – he used them simply, yet with as much care as if they were luxurious materials. Harris built on what went before and took it further.

Placed alongside the work of John Lautner, Lloyd Wright, Gregory Ain, and A. Quincy Jones from the same year, the Blair house demonstrates the astonishing range of ideas that constitute modernism in California. It even appears to be prescient about the future of California architecture: In the top floor studio’s shed roof you can see the revolutionary shed roofs to be popularized by Moore, Lyndon, Turnbull and Whitaker at Sea Ranch 30 years later. In this design, however, the clients added a unique dimension. The Blairs were Southern Californians who had painted every aspect of the region, from the cliffs overlooking the ocean beaches to the slums of Bunker Hill to the Okie migrant camps of the Depression years. They chose their house’s site for its peaceful rural beauty, and yet it was just minutes from the animation studios for which they worked, on the leading edge of popular technology and culture. The delightful and surprising quality of light captured throughout the house as the sun moves across the sky would not be lost on these artists. The way Harris overlaps three dimensional space is as freshly modern as the way Mary Blair used cubist concepts to flatten traditional Renaissance perspective in her paintings. Her work links Disney’s mass audience modernism with high art culture without diminishing either.