It’s like being in Switzerland: You want to see the Matterhorn,” says Crosby Doe a veteran salesman of architecturally significant houses. And when in Palm Springs, he adds, “You want to see the Kaufmann Desert House.”

That kind of fame can have its drawbacks, however, especially for the person in charge of selling a house that nearly eveybody, it seems, wants to see. Out of self-defense — and consideration for the owners, who still occupy the residence — Doe came up with a Draconian test-to sift the gold from the sand. “I tell them,” he says with the modulated tones of a man who for 30 years has sold houses by big-name architects, “that they can see the house, if they can qualify to pay for it.” The property is listed for $12 million. Boom! The crowd suddenly gets much smaller. Even Hollywood types are thin on the ground.

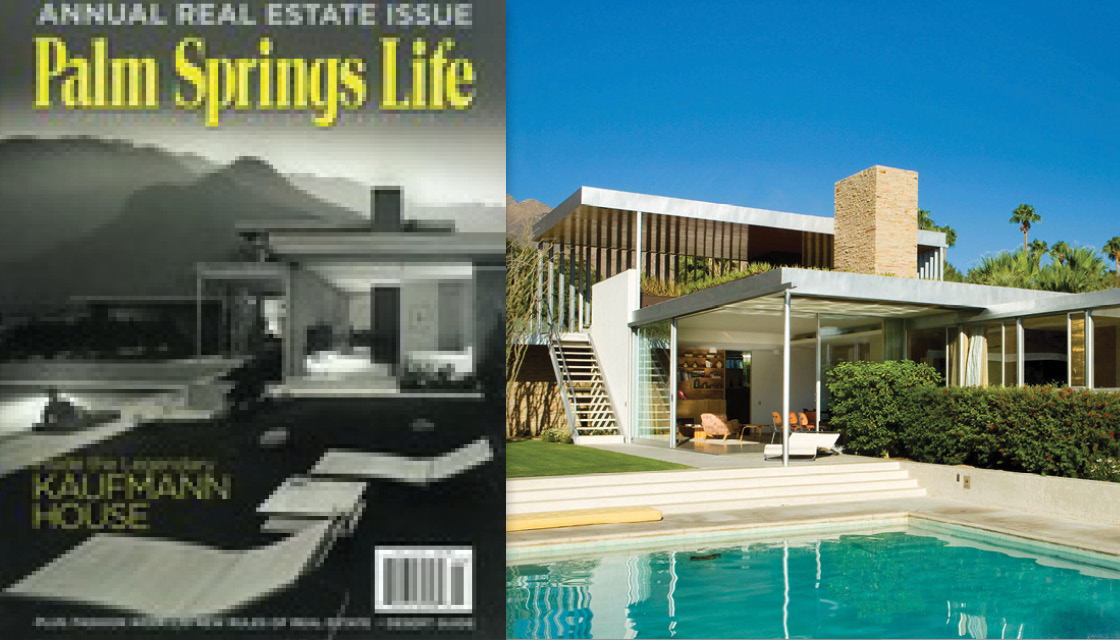

Doe can hardly blame the enthusiasts, even those who, in the current down turn in the housing market, can barely afford their own houses, much less the former vacation house of Pittsburgh department store magnate Edgar J. Kaufmann. The much-photographed 1946 masterwork by architect Richard Neutra might be the happiest marriage of the abstract geometry of modern architecture with the desert-and-mountain landscape of Palm Springs. The sleek, largely horizontal, 3,162-square-foot house — situated on 2.53 acres, and including five bedrooms and six bathrooms — is laid out with pinwheel-like wings, offset by a few vertical elements — a chimney and an outdoor sleeping area that Neutra called a “gloriette” — that pull together the sprawling compositing.

The house represents a special moment in the Neutra canon, when the architect was able to blur the distinction between inside and outside to an unusual degree, according to architectural historian Barbara Lamprecht, It is “not so much a house with an indoors and an outdoors,” she writes in an essay commissioned by Doe. “Rather, it is a setting with transitions in which Neutra honed both nature and the functional aspects of living so that Eros, sensuality, the senses are subtly and/or overtly available to the whole arc of day and night and the whole spectrum of being.”

Not surprisingly, given a client like Kaufmann, the house was also a luxe job. Plans of tawny Utah stone mingle with industrial materials like steel and silver-painted aluminum. And rather than the white interiors that Neutra had favored in earlier projects, the interior colors here, in Lamprecht’s rendition, are “rose, green, canary yellow, salmon,” all set against white and the dark, neutral color that the historian calls “infamous Neutra brown” that the architect used to make certain walls appear to recede behind others. For the Kaufmann house, the painstaking Neutra may have had a client as demanding as the architect himself: To finish the home, Kaufmann employed three crews, working 24 hours a day. He had a personal representative on the site, on the phone constantly with him, and drove up costs insanely with 600 change orders. A house originally priced at $35,000 — a pretty penny in the lean years immediately following World War II — ballooned to $295,000.

When Brent and Beth Harris bought the house for about $1.5 million in 1993, both its interior and exterior had suffered damage due largely to heat. (The house stood vacant after Kaufman died in 1955 and was remodeled by subsequent owners, including Barry Manilow.) The Harrises hired Los Angeles-based Marmol Radziner and Associates to refurbish to the house, sparing no expense and relocating original materials and manufacturers whenever possible. The reconstruction budget, never made public, was rumored to be in the seven-figure range. Images of the revived Kaufmann Desert House, together with the famous images taken of the original structure by photographer Julius Shulman, did more than help put Palm Springs modernism back on the map: The restoration of the house helped launch the vast middle-brow enthusiasm for what came to be known as “midcentry modernism.:” Modernism, long reviled for highbrow inaccessibility, had finally become a brand.

After the Harrises divorced several years ago, they decided to sell the house. The first effort was a widely publicized auction last year at Christie’s, the New York auction house, where the modernist gem sold for a breathtaking $19.1 million. The sale would later fall out of escrow, however, for unknown reason. At press time, the house was listed at slightly below $13 million.

Even though Doe is selling the house the old-fashioned way, by walking prospective buyers through the property one by one, he does not disparage the headline-grabbing method of selling rare houses at public auction. “It was not a stunt,” he says in defense of the sale at Christie’s, pointing out that several other modernist properties, including a Pierre Koening in Studio City and the Farnsworth House in Plano, Ill., both fetched higher prices at auction than could be achieved in conventional sales. Doe, in fact, says he ran into Beth Harris the day after the auction, and opined he “could not have done a better job of marketing.” When the auction sale fell through, the Harrises turned to Doe.

Given the high-stakes elimination of looky-loos, how many genuine prospective buyers have toured the house to date? “About a half dozen,” Doe says. They come from all over the country, primarily the Midwest, he says. “They are mostly CEO types. Two are art collectors, and another one does a lot of philanthropic work and is interested in architecture.” Few people from the entertainment industry have shown up, which surprised Doe: Hollywood has long been a mainstay of support for California modernism, particularly in Palm springs.

If walking the rich through Palm Springs’ most exclusive house is a privilege, it is also wistful. The Harrises, who reportedly share the house on alternating weekends, may not be happy about parting with the house they have done so much to preserve.

“Although it is one of the treasures of the world of modernism, I get certain pangs whenever I show it,” Doe says. “I sense”, he adds, “a reticence on the part of the owner about letting it go.”

(Article was transcribed from the Palm Springs Life- Annual Real Estate Issue – May, 2009)