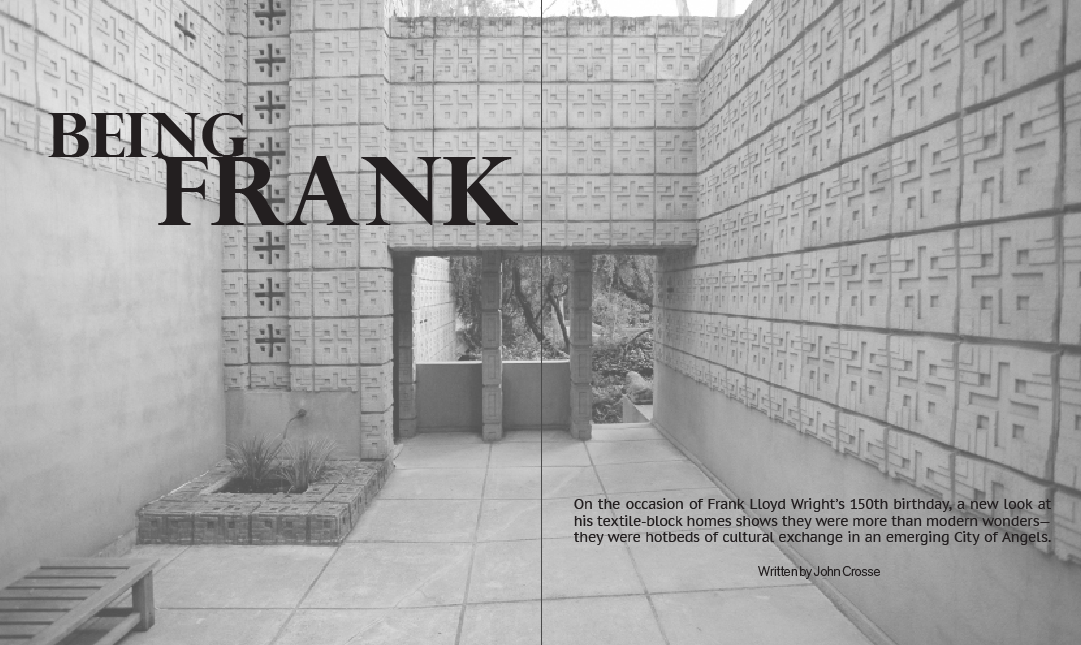

Being Frank

On the occasion of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 150th birthday, a new look at his textile-block homes shows they were more than modern wonders—they were hotbeds of cultural exchange in an emerging City of Angels.

by John Crosse

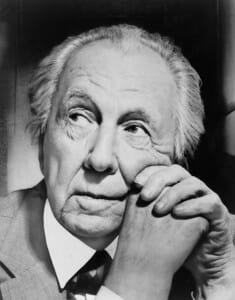

Much has been written about Frank Lloyd Wright’s Mayan-inspired Southern California architecture of the early 1920s. Yet, relatively little is known about his West Coast sojourns and his relationships with the bohemian denizens who lived in his remarkable Los Angeles homes. So what better time than now—the sesquicentennial year of Wright’s birth (June 8, 1867)—to take a deeper look at the avant-garde personalities that elevated his unique structures to a higher plane.

All of Wright’s Southern California houses have fascinating back stories. But four in particular—the Barnsdall, Millard, Storer and Freeman houses—provided important venues for the cross-pollination of cultural activity that took place in Los Angeles during the twenties and thirties.

Most historians would agree that Wright’s commission for oil heiress Aline Barnsdall was not only a visionary work, but was perhaps the first step in the progression of Los Angeles’s modern architectural and cultural history. In Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography, the architect reminisces, “Now, with a radical client like Miss Barnsdall, a site like Olive Hill, a climate like California, an architect head on for freedom, something had to happen, even by proxy. So this Romanza of California came out on Olive Hill.”

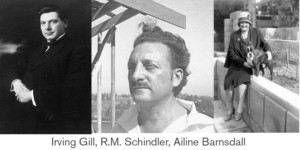

While commuting back and forth between Taliesin and Tokyo to bring his Mayan Revival Style to Japan’s Imperial Hotel, Wright visited Southern California numerous times. In 1913, he rendezvoused there with sons Lloyd and John and their mentor, Irving Gill, his former Sullivan office colleague. He again reunited with Lloyd, Gill and Midway Gardens assistant Alfonso Iannelli in San Diego in early 1915 to visit the city’s Panama-California Exposition (this was during his recuperation from the tragic events surrounding the 1914 fire that destroyed his Wisconsin home, Taliesin, where his mistress, Mamah Cheney, her two children, and four Taliesin guests where murdered by a mentally unhinged servant as they fled the blaze). The Exposition’s Pre-Columbian Central America exhibits, including the models of the Mayan temples of Uxmal and Chichen Itza, clearly inspired Wright’s 1918-24 Los Angeles oeuvre.

But it was Aline’s earlier 1915 visit to San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition that anticipated her association with Wright. A year later, she selected Los Angeles as the location to fulfill her lifelong dream of creating a theatrical colony. While beginning discussions with Wright on a theater design, she rented a temporary space to launch her Los Angeles Little Theatre. She gathered together a well-regarded troupe which included Chicago Little Theatre star Kyra Markham with whom Lloyd Wright, then a set designer at Paramount Studios, became infatuated and married in November 1916.

This created the impetus for Barnsdall to commission the senior Wright to design her personal residence, an unrealized theater, a director’s residence and related buildings to provide a permanent home for her Players Producing Company. She purchased Olive Hill in 1919 and the design and construction of her Hollyhock House and Residences A and B were completed by the fall of 1921 under the construction supervision of the young architect, R. M. Schindler, whom Wright had summoned from Chicago the previous December.

Upon completion of the Imperial Hotel, Wright returned to Southern California in 1923 with hopes of finding a fresh start. He and son Lloyd opened a design atelier on Harper Avenue in West Hollywood which was staffed by his Imperial Hotel associates, Kameki and Nobu Tsuchiura, and Will Smith from his Chicago office. He rented Residence B from Barnsdall and founded the short-lived Fine Art Society which led her to lease the Hollyhock House to the California Art Club in 1927 (meanwhile, his Residence A neighbors were noted art collectors, Walter and Louise Arensberg, who were freshly relocated from New York, another harbinger of the CAC inhabitancy).

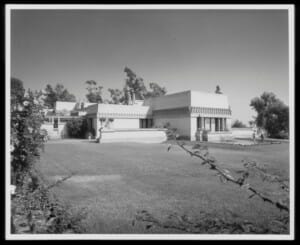

From this base, Wright soon convinced Alice Millard to commission a home in Pasadena which would become known as La Miniatura (it would also become one of his favorite houses).

Alice Millard continued dealing in rare books after the 1918 death of her husband and would branch out into antiques, paintings, sculpture, tapestries and related finery brought back from annual European buying trips. The indefatigable tastemaker hosted salons and staged exhibitions in a relentless quest to educate allegedly provincial Southern Californians in all things beautiful. Wright described the doyenne of arroyo culture as the “heroine of this story: slender, energetic—fighting for the best of everything for everyone.” Her success gave her the confidence to entrust Wright with the design of “nothing less than a distinctly genuine expression of California life in terms of modern industry and American opportunity.”

By the 1930s, Millard could boast such important library-building clients as Estelle Doheny, Henry Huntington, Templeton Crocker, William Andrews Clark and Walter Arensberg. Her reputation among the well-heeled intelligentsia was such that she was able to invite the likes of Albert Einstein, in residence at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), to dine with her and Wright at La Miniatura in 1931.

During Wright’s attempt to establish his practice in Los Angeles in 1922-23, progressive educator Leah Press Lovell and Rudolph Schindler’s wife, Pauline, were helping form a kindergarten for Barnsdall’s daughter Betty and some neighborhood children. About the same time, Leah’s teacher-cum-dancer sister Harriet and jeweler-husband Sam Freeman visited Leah on Olive Hill and were so impressed by Wright’s work, that they immediately selected him to design their hilltop Hollywood home near the corner of Franklin and Highland avenues. The house was completed by Lloyd in March of 1925 after Frank returned to Taliesin in 1924.

Like the Schindlers and their unorthodox Kings Road home in West Hollywood, the Freemans regularly opened their Wright manse to a coterie of like-minded bohemians, which provided another serious venue for cultural exchange. The Freemans also became close with photographer Edward Weston and mutual artist friends such as Gjura Stojana, Franz Geritz, Boris Deutsch and Peter Krasnow; also included were Roscoe and Bess Shrader and Conrad and Mary Buff who were officers in the California Art Club and Hollywood Art Association with the Schindlers and connected to the Otis Art Institute and the Los Angeles Museum of Art.

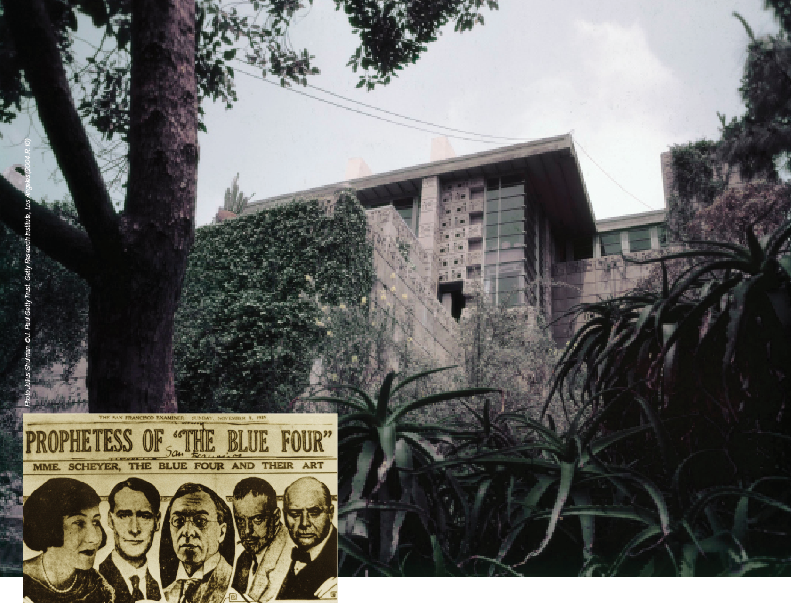

The noted painter and art dealer Galka Scheyer, who brought the work of the “Blue Four” (artists Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Alexej Jawlensky) to the United States, hosted many promotional salons while living with the Freemans in 1927. She continued to hold such soirees in their new Schindler-designed guest apartment in 1933, before moving into her own Richard Neutra-designed home in the hills where she entertained Wright, Weston, Aline Barnsdall and others.

Harriet also closely bonded with the circles surrounding Weston dance clients Marion Morgan, Norma Gould, Ruth St. Denis, Martha Graham and Bertha Wardell who taught dance and physical education at UC-Southern Branch (later UCLA) alongside Pauline’s sister Dorothy Gibling. Weston has written of dancing with Harriet at one of her countless soirees: “Harriet dances well: if she were smaller—in bulk—she would be ideal for me. We danced many times to exquisite Spanish tangos.”

Another close friend of the Freemans was UCLA art instructor Annita Delano who has said: “Schindler and Neutra came to Los Angeles to work with Frank Lloyd Wright, and I was privileged to know them right away within the first year after they came here. It seems the architects, designers, painters, sculptors got together. The city was so much smaller. We met in a Frank Lloyd Wright house—that is, the Freeman House in Hollywood. It was tremendous to have this get-together with people who were creating. And that’s how I got interested [in modern architecture].”

Around the time the Freemans were getting settled, Barnsdall was tiring of Olive Hill and donated her hilltop to the City of Los Angeles for an art park. In 1927, she gave the California Art Club a 15-year lease for use of the property as a clubhouse and exhibition venue. Architect members of the club, including Neutra, Schindler and Kem Weber, were involved in designing modifications to create viewing galleries for their frequent exhibitions.

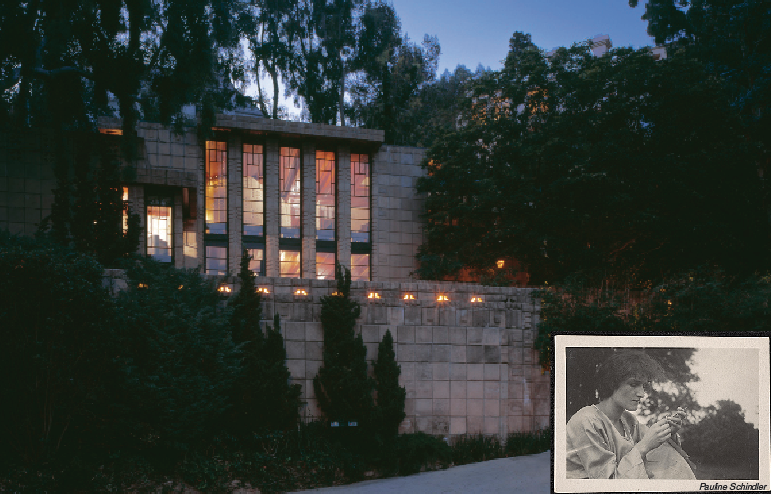

Just as the California Art Club was organizing its inaugural exhibition on Olive Hill (including a Schindler-designed exhibition of Barnsdall’s travel posters), the Schindlers separated. Pauline spent the next two years in Carmel publishing and editing the local progressive weekly, The Carmelite, naming to her editorial advisory board Edward Weston, Richard Neutra, Galka Scheyer, Carol Aronovici, Lincoln Steffens, Ella Winter and others. She returned to Los Angeles in early 1930 with ambitious plans to market the work of Schindler (though they were estranged), Neutra, Kem Weber, J. R. Davidson, Jock Peters and Frank Lloyd Wright and to author a book on modern architecture. She eagerly established her headquarters in Wright’s Storer House on Hollywood Boulevard in the hills above Sunset, which her husband had remodeled in 1925.

Moving in with her shortly thereafter were Edward Weston’s son, Brett Weston, a talented photographer in his own right, and Galka Scheyer. The fledgling lensman established his first studio on the ground floor and was quickly commissioned to photograph L.A. work by Wright, Schindler and others for Pauline’s first project, a groundbreaking exhibition she titled Contemporary Creative Architecture of California. This was not only the first independent exhibition of Wright’s work, but it was solely focused on “modern” architecture and would precede the seminal 1932 MoMA show, Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, by a full two years.

The exhibition traveled among various West Coast venues during 1930-31. Pauline also began acting as Brett’s agent and designed his business card featuring Brett’s portrait of their mutual Carmel friend Vasia Anikeef. Pauline and housemate Galka Scheyer, the first person to ever purchase a Brett Weston print, would commandeer Harry Braxton’s nearby Hollywood gallery (designed by Pauline’s estranged husband), to show wealthy prospective clients Brett’s work. Despite his fondness for that period of his life, the photographer called the Storer residence “a Frank Lloyd ‘Wrong’ house. Horrible to live in. Nothing worked right, but it looked good. He never built a house people could live in.”

Filmmaker Josef Von Sternberg (The Blue Angel, Shanghai Express), who was to own one of Neutra’s most famous (and later, tragically demolished) houses, helped sponsor a series of Blue Four exhibitions that Scheyer organized at the Braxton Gallery (where Edward Weston, Peter Krasnow and others in their circle also exhibited in those days), hoping to finally make inroads with well-heeled Hollywood collectors. The exhibitions ran concurrently with Pauline’s exhibitions at UCLA and the California Art Club.

Meanwhile, Brett’s portrait clients during 1930 included his amigo, Mexican painter Jose Clemente Orozco, in town for a fete at the California Art Club upon completion of his Prometheus mural at Pomona College, and also Soviet director and theorist, Sergei Eisenstein, who was collaborating on a film with the writers Upton Sinclair and Weston family friend Seymour Stern.

During her two-year stay in the Storer House, Pauline maintained an active schedule of salons, published dozens of articles promoting the work of her “contemporary creators” and artist friends, ran a business selling children’s toys, taught a graphic design class at USC, and co-edited the arts and crafts magazine The Handicrafter in which she featured the work of Weston, Peter Krasnow and Kings Road tenant John Bovingdon, among others. In 1931, she also organized a second modern architecture and interior-design exhibition at the Plaza Art Center in conjunction with the restoration of downtown’s Olvera Street and the La Fiesta celebrating L.A.’s own sesquicentennial.

Wright’s last project in Los Angeles was fittingly an exhibition pavilion on Olive Hill designed to house his traveling exhibition, Sixty Years of Living Architecture. It brought his involvement on Olive Hill full circle; the show was attended by a virtual who’s who of the L.A. arts community—artists, patrons and aficionados who had spent their formative years attending exhibitions, salons, recitals and parties in the Barnsdall, Millard, Freeman and Storer Houses. Many were no doubt imbued with and inspired by Wright’s unique brand of inventiveness and imagination.

It is no mere coincidence then to find that these four Wright houses in Los Angeles have all been declared local Historical Cultural Monuments and are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The Aline Barnsdall complex on Olive Hill—now more commonly known as Barnsdall Park—was granted National Historic Landmark status in 2007. And upon completion of a major restoration effort in 2015, it was nominated for designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site—a fitting honor for the place where so much cultural exchange started in the City of Angels.

In his own way, the legendary architect provided a foundation for the people of Los Angeles to celebrate the arts. It was a byproduct of his genius—and as good a reason as any to celebrate 150 years of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Contact us about this property:

Error: Contact form not found.