The Lost Niemeyer

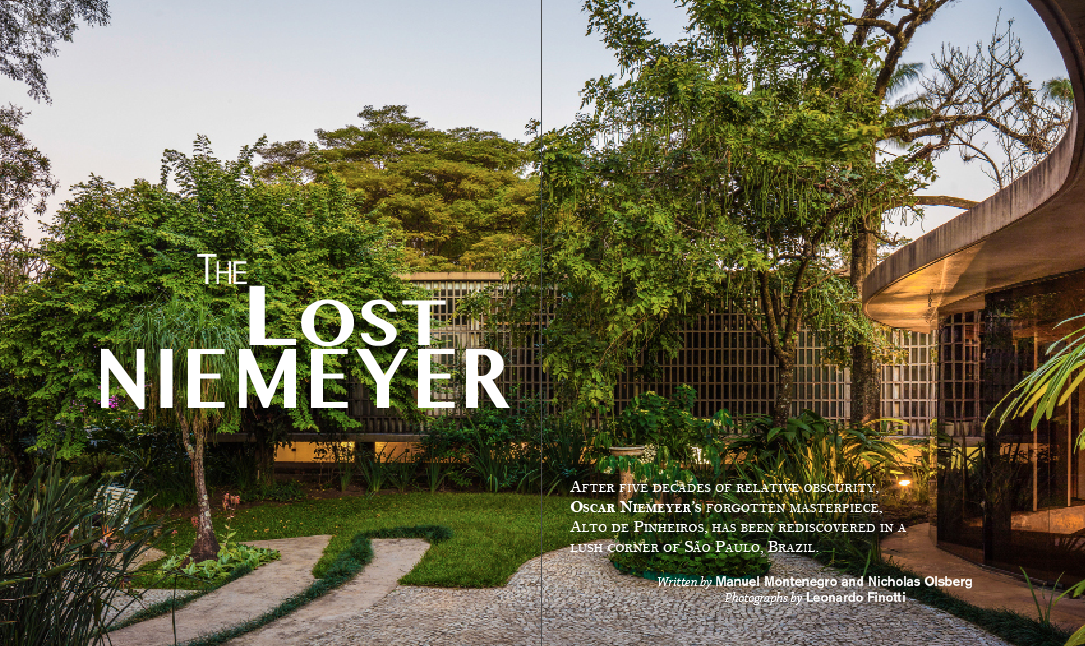

After five decades of relative obscurity, Oscar Niemeyer’s forgotten masterpiece, Alto de Pinheiros, has been rediscovered in a lush corner of São Paulo, Brazil.

by Manuel Montenegro and Nicholas Olsberg

Tucked inside one of the leafy Garden City developments near the Pinheiros River in western São Paulo, sits a fairly inconspicuous semi-urban villa built in 1974 for a prosperous Brazilian family. The 7,000-square-foot abode includes five bedrooms, a wine cellar and garage space for six cars. From the street, all you can see is the rear of a hovering monolithic concrete volume that forms the bedroom wing and covers the carport. Most of the house opens to the garden behind it, the main living space hidden among the lush plantings of legendary landscaper, Roberto Burle Marx.

This is Oscar Niemeyer’s Alto de Pinheiros residence. It’s not as famous as his 1953 Canoas House, a free-form masterpiece that Niemeyer built for himself on an ocean-view slope, or even his celebrated1954 Cavanelas house with its tent-like metallic roof that blends into the mountainous site (also with the help of Burle Marx-designed gardens). But this hidden gem nonetheless bears all the signs of a fully mature late work by an internationally renowned master at the peak of his powers.

In a quiet and almost contemplative fashion, the house returns to and synthesizes many of the fundamental features that made Niemeyer—who created the curved, concrete Edificio Copan apartment tower in downtown São Paulo, as well as so many boldly innovative public buildings in the then-new capital city of Brasilia—such a central figure in the development of the international modern movement. At its most essential, the home seems to recall its creator’s quest for a more fluent, natural and expressive approach to modernity.

So it is all the more remarkable that a work of such importance and magnitude by a figure of worldwide significance could sit almost unrecognized for over 40 years-—until recently when the house hit the real-estate market for the first time. Till now, it has been vaguely known to exist by scholars and only the most dedicated of architecture aficionados. And though it has been in the same family all this time—remaining a compellingly complex, seductive and sensitively imagined work—even the Niemeyer Foundation hadn’t listed the project in their catalogue of his buildings.

Put into the context of its time, though, such anonymity is understandable. In the mid-1970s when Alto de Pinheiros was built, Niemeyer’s career had been tarnished by his involvement with the Brazilian Communist Party. Having left his homeland after the 1964 military coup and opened in an office in Paris, he did not return to Brazil till 1985. And though he had been invited by Brazil’s president, Juscelino Kubitschek, in 1956 to create the civic buildings for Brazil’s new modern capital city of Brasilia—which were to include experimental designs for the National Congress of Brazil, the Cathedral of Brasília, the Palácio da Alvorada, the Palácio do Planalto, and the Supreme Federal Court, all designed by 1960—he was not awarded the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize until 1988.

So throughout this time, the Alto de Pinheiros residence was not appreciated as the final testament it was to the more intimate, inventive and sensitive approach to building that had always taken a place alongside his more assertive public work. This style was also lost in later years upon his return from Paris to Rio de Janeiro as his studio turned to more grandiloquent statements, like his clifftop Niteroi Contemporary Art Museum, which opened in 1996 overlooking Guanabara Bay.

Another key reason for the house’s relative obscurity was its owners’ ongoing desire for privacy. As a result, it has fallen, like a ruminative late Schubert sonata, quite off the radar. Its recent rediscovery should be an occasion for celebration and a reminder that (especially in his collaborations with landscaper Burle Marx), there was in Niemeyer just as much passion for the private—for serenity, for contact with nature, for the colors of life, and for the shaping of movement in living—as for the grander expression of public life that marks the works for which he is revered.

Born in 1907, Oscar Ribeiro de Almeida Niemeyer Soares Filho graduated from the Escola Nacional de Belas Artes at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in 1934. Soon, he interned with Lucio Costa, quickly rising to be the most recognized and admired figure in the emerging South American movement towards a new architecture—one of the earliest and most vibrant chapters in modern architectural history. In 1936, he was part of the team from Costa’s office that designed a building for the new Ministry of Education and Health Care in Rio, one of the first major modern public buildings in the world. Le Corbusier acted as a guest consultant, and Roberto Burle Marx made his first distinctively personal contribution to the history of landscape architecture.

Worldwide acclaim as Brazil’s most important architect came at an early age—Niemeyer was awarded the Medal of the City of New York as part of the team that designed Brazil’s pavilion for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Returning home the following year, he started his long collaboration with Kubitscheck, then mayor of the city of Belo Horizonte, who commissioned him to design the masterplan and community buildings for the new suburb of Pampulha. Between 1940 and 1944, he built a casino, yacht club, dance club, and chapel (Burle Marx also designed the landscape). In addition to his work for the Ministry of Education and Health Care, the construction of Pampulha signalled the importance of Brazil, and of Niemeyer and Burle Marx in particular, in moving modernism from the realm of hypothesis and random monuments into the larger built world. As Niemeyer stated clearly, the Brazilian movement also radically widened the possibilities of modernism:

“The project [of Pampulha] was an opportunity to challenge the monotony of contemporary architecture, the wave of misinterpreted functionalism that hindered it, and the dogmas of form and function that had emerged, counteracting the plastic freedom that reinforced concrete introduced. I was attracted by the curve—the liberated, sensual curve suggested by the possibilities of new technology yet so often recalled in venerable old baroque churches.”

Elizabeth Mock’s 1943 MoMA exhibition, Brazil Builds, highlighted the innovative expressionist designs for Pampulha, placing them amid the long tradition of building derived from the Baroque churches of colonial Minas Gerais and crowning Niemeyer as one of the strongest voices in architectural practice. The exhibition was carefully timed to appear at a moment when Europe and North America—though still engulfed in war—began to envision the character of a post-war world, with Brazil’s example clearly held up as a model for the world to follow. As a result, Niemeyer was invited to the United States in 1946, almost as soon as the war ended, to present his approach to modern architecture in lectures at Yale.

After being initially denied a visa to enter the United States because of his leftist leanings, his overriding importance to international architectural culture eventually prevailed. A year later, he was welcomed to the U.S. and spent seven months in New York, where he became the lead architect on the United Nations headquarters, adding its unmistakable contours to the city skyline. Though the final design was undertaken by Harrison and Abramovitz, and was tempered by some concessions to the requests of Le Corbusier, the fundamental separation into distinct but linked structures—one linear and mathematical, the other employing a sweeping curved geometry—was Niemeyer’s conception. The very same factors, worked at very different scale and with more delicacy, is echoed in the Alto de Pinheiros house.

Around the time of his presence in New York, Niemeyer was commissioned to design a large-scale seaside house in Santa Barbara, California. In the Burton Tremaine residence, Niemeyer returned to the experiments he developed in Pampulha, in which individual buildings of different character become united across a widely dispersed landscape. Together with Burle Marx, he drew them into a compact whole, creating a perfect synthesis of his understanding of the place of architecture within the terrain. Here, Pampulha’s chapel becoming the car park; the city’s yacht club, the private quarters; and its dance club, the covered social areas. It was something he had previously developed as a strategy for the unbuilt Hotel of Pampulha, but here reduced in scale to its most basic unit.

The Tremaine design was, in effect, a comprehensive manifesto of his approach to architectural design, and its importance was widely and immediately recognized, leading to the exhibition From Le Corbusier to Niemeyer, 1929–49 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Curated by American architect Philip Johnson, the exhibition traced the evolution of modern architecture toward a new and more expressive language through two single works: The already iconic masterpiece of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye and Niemeyer’s proposed Tremaine House on the bluffs of Montecito.

Though the house remained unbuilt, the ideas behind this hugely important project were heralded in a seminal issue of Arts & Architecture and were echoed decades later in the house at Pinheiros. As John Entenza wrote of the Tremaine House, “The recent project for a California beach house by the young Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer is the culmination of thirty years of development in architectural design. This house represents today’s final synthesis of two important Twentieth Century stylistic trends: the strict mechanical formalism of Le Corbusier and the Cubist-Constructivist movement, and the organic shapes and free form fantasy of the tradition of Miro and Arp.”

A second close collaboration with his patron Kubitschek, now the head of the Brazilian state, brought Niemeyer what was arguably his most audacious commission: Lucio Costa was named the urbanist for Brasilia, the nascent capital of a now rapidly modernising country. Most of the public buildings, from 1957 onwards, were to be designed by Niemeyer himself, and the public landscaping again by Burle Marx. They were designs that were emblematic of the idea that Brazil was a country racing into the future.

This triumphal march toward a gleaming tomorrow was abruptly halted by the military coup that seized power in 1964 and ruled the country for the next 21 years. During this time, Niemeyer, openly communist and an enemy of the new regime, abandoned his teaching at the University of Brasilia after protesting the invasion of its premises by the military in 1965. Ultimately, he found it impossible to work and left for Paris, where he opened an office in the Av. des Champs-Elysées in 1967. His most important public and private commissions at that time were mostly outside Brazil.

Alto de Pineiros was designed during these troubled times for Brazil, when Niemeyer was living in Europe and working on projects in France, Italy, and Portugal, not to mention North Africa and the Middle East (including Algeria, Lebanon, and Israel).

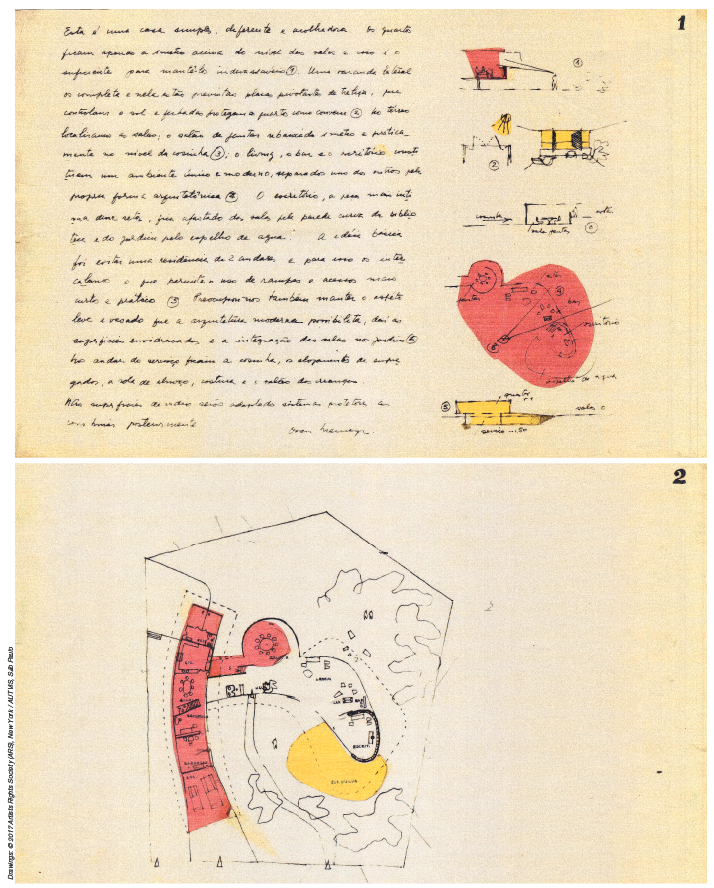

Little is known about the history of this design. All that remains of it, besides the actual building, is a small sketched presentation set of the house, most likely produced before construction began in 1970, as well as a personal letter from Niemeyer to the client, dated 1976, in which he seems to imply the house was largely finished.

In his presentation, Niemeyer explains his plan both in concept and detail, providing numbered sketches to illustrate how it will work. “This is a simple, deferential and welcoming house,” he says. It was designed to be responsive to the family’s needs and lifestyle. In order to obtain a more fluid space than is possible in a two-story house, the residence was organized in two segments: A long horizontal wing, in which the private quarters and bedrooms are raised above a service floor and parking and a free-form pavilion of interlocking, open-plan living space that extends out from this wing to wrap around the garden and its pool.

He goes on to explain in detail how each idea will work in the numbered sketch diagrams (two of which are seen opposite): “The bedrooms are raised one meter above ground level on the garden side. This is just high enough to keep them private. A porch along the side completes them. There are trellis slabs on the porch that pivot to control sunlight, and can, when fully closed, provide shelter to the rooms as required. On the ground level we find the reception and family rooms. The dining room is lowered one meter so that it can function practically on the same level as the service kitchen. The adjacent living room, bar and study constitute a distinctive modern environment of their own, separated from each other by the shape of the architecture itself. The study or writing room, the most intimate part of this sector, is divided from the other spaces through the curved wall of the library, and separated from the garden by a pond. The basic idea was to avoid laying out living space on two stories. To achieve this, we employed the notion of interlocking spaces, with shallow ramps and short passages or flights of steps to allow for easy movement between them. We also took care to maintain the light and airy appearance that modern architecture makes possible–hence the glazed surfaces and the integration of the principal indoor living spaces with the gardens. On the service floor are located the main kitchen, the employee quarters, the lunch room, the sewing room and the children’s room. A security and protection system for the glass surfaces will be developed at a later date.”

From Niemeyer’s schematic section, we can read how the principal living spaces are level with the gardens, a half level above the service area and a half level below the bedroom area, providing varying degrees of privacy to the different spaces of the house, both from inside and from the grounds. The only space that interrupts this clear logic, and one that Niemeyer highlights in the presentation set, is the circular dining area, which is at the level of the service area but already under the free-form canopy with the vertical circulation wrapping around it in a snail-like composition reminiscent of Mies van der Rohe’s famous Tugendhadt dining space (a comparison reinforced by the wood veneer covering the circular walls in Niemeyer’s sketches, that can also be seen in Mies’ space).

The general scheme of the house follows the same efficient strategy outlined by Niemeyer for most groups of his larger public buildings: Some form of stable, grounded block that anchors the ensemble (and mostly contains all the services and secondary spaces) from which emerges an organic, free-form horizontal plane that provides a cover for a single level of united social space, fully glazed and connected to the outside gardens and landscape, like an extended porch or pavilion. It can be seen in his works for Pampulha, notably in the dance club roof structure, and in the Canoas House, where the “grounding block” is half-buried in the hillside and literally serves as a horizontal base for the free-form plane that is given center stage as it wanders into the gardens.

Niemeyer explores this idea of fluid space emerging from a fixed base to its fullest extent in his house designs, where his annotated sketches outline the theory behind this approach. This starts most notably with the Burton Tremaine House and is developed two decades later in the built version of the Mondadori House, in St. Jean de Cap-Ferrat, France (1968), a project that immediately preceded this work in São Paulo.

Niemeyer died in 2012, living to the age of nearly 105; he was still active in design and reconsidering the politics of space until the very end. He is, increasingly, one of the central and more fascinating figures in the history of twentieth-century architecture, spearheading the artistic contribution of the Southern Hemisphere to the modern movement in architecture from the late 1930s through the 1940s. His determination to introduce fluent forms and a more fluid approach to space—in such works as his Brazilian pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair and his designs for the United Nations building in 1947—answered the hunger for a newly natural and more expressive approach to modernity. He went on to become a fundamental source of inspiration for some architects of the late fifties—e.g. John Lautner—who rebelled against the discretion and quietude of New Humanism. Like Niemeyer, they sought bolder gestures and more sweeping forms to express the growing freedom of the Space Age and its aspiration to place architecture and life in greater resonance with the grandeur of the earth and skies.

Though Cold War prejudice dampened his career and visibility for a time, Niemeyer reemerged in the sixties as an influential figure in international culture, as his conception of Brasilia, with its huge vistas, open plazas and supple monuments, captured the imagination of an entire generation intrigued by a fresh and transcendental future.

We can see all of this in Niemeyer’s low-profile house at Alto de Pineiros. Here, in this strangely forgotten masterpiece, the Brazilian architect worked with Roberto Burle Marx to bring many of his most important and original ideas—the fluent connection of space to space, the union of built form with landscape, the balance between practicality and romance, as well as the mathematical and the biomorphic—to a triumphant conclusion. There is no doubt of his own assessment of the result. As Niemeyer wrote to the original client after seeing it, perhaps for the first time, six years after its inception: “I can only imagine the effort this house meant for you. It is something we do only once in a lifetime.”

Contact us about this property:

Error: Contact form not found.